Indeed, where did coal come from?

This question may seem naive at first. Every diligent student will say without hesitation: coal is a substance of plant origin, "a product of the transformation of higher and lower plants" (Soviet encyclopedic dictionary of all editions). Not a single textbook, not a single popular book questioned this truth. At school we were firmly convinced in the chain: "plants - peat - brown coal - coal - anthracite" … Well, let's take a closer look at the textbook theory of coal formation.

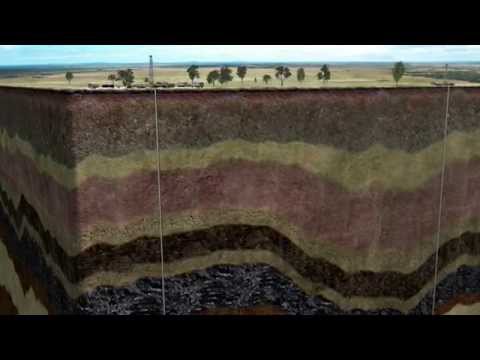

So, in a certain stagnant reservoir, organic matter rots. Peat is gradually formed from the plant mass. Diving deeper and deeper, being covered with sediment, it becomes denser and as a result of complex chemical processes, saturated with carbon, turns into coal. Peat practically does not react to a small load of sediments, but under powerful pressure, dehydrating and compaction, its volume can decrease many times - something similar happens when pressing peat briquettes.

Nothing new, just like that they write everywhere. However, now let us pay attention to the following circumstance. The peat deposit is surrounded by sedimentary rocks that experience the same vertical loads as peat. Only the degree of their compaction cannot be compared with the degree of compaction of peat: sands hardly decrease in volume, and clays can lose only up to 20-30% of their original volume or a little more. Therefore, it is clear that the roof over the peat deposit, as it compresses and turns into coal, will sag and a sinkhole fold will form over the "newly minted" coal seam.

The dimensions of such folds should be very solid: if a ten-centimeter coal seam is obtained from a meter-long peat layer, then the amplitude of the fold deflection will be about 90 cm. Equally simple calculations show that for coal seams and layers of any thickness and composition, the dimensions of the expected folds are so large that it would be impossible to notice them - the amplitude of the dip will always exceed the thickness of the formation itself. However, here's the problem: nm did not have to see such folds, nor read about them in any scientific publication, both domestic and foreign. The roof over the coals is calm everywhere.

This means only one thing: the parent material of the coals either did not decrease in volume at all, or decreased as insignificantly as the surrounding rocks. Therefore, this substance could not be peat in any way. By the way, the reverse course of the analysis leads to exactly the same conclusion. If, with the help of a pencil and paper, we try to restore the initial position of the cuts at the moment when the peat has not yet turned into coal, one can be convinced that such a problem has no solution, it is impossible to construct a cut. Anyone can be convinced that layers of the same age will have to be torn apart and placed at different heights - in this case, there will not be enough layers, awkward bends and voids will appear, which in fact does not exist and cannot be.

No, even a very reasonable single remark or study can not cancel the established scientific views, especially if they are more than one hundred years old. Therefore, let's talk a little more about peat shrinkage. It is calculated that when brown coal is formed, the coefficient of this shrinkage is on average 5-10, sometimes 20, and even more when coal and anthracite are formed. Since the vertical load acts on the peat, the layer is, as it were, flattened. We have already said that from a meter-long peat layer a brown coal layer with a thickness of one decimeter can be obtained. So what happens: the unique Hat Creek coal seam in Canada, with a thickness of about 450 m, gave rise to a peat layer 2 to 4 km thick?

Of course, no one is forbidden to assume that in ancient times, when much on Earth was considered to be "larger", peat bogs could reach such cyclopean sizes, but there is absolutely no evidence in favor of this. In practice, the thickness of peat layers is measured in meters, but never in tens, not to mention hundreds. Academician D. V. Nalivkin called this paradox mysterious.

Promotional video:

The largest amount of fossil coals was formed at the end of the Paleozoic era, in the so-called Permian period 235 - 285 million years ago. For those who believe in textbooks, this is strange, and here's why. In the luxurious Czechoslovak gift albums of Augusta and Burian, one can see colorful pictures depicting the dense, impenetrable horsetail-fern forests that covered our planet in the preceding Permian Carboniferous era. There is even a term: "coal forest". However, until now, no one has really answered the question of why this forest, despite its name, did not give so much coal as arid and plant-poor Perm.

Let's try to dispel one surprise with another. In the same Permian period, the most generous for coals, deposits of rock and potassium salts arose in the same coal regions. Where there is a lot of salt, nothing grows or grows with great difficulty (remember salt marshes - a kind of desert). Therefore, coal and salt are considered to be antipodes, antagonists. Where there is coal, there is nothing to do with salt, they never look for it there - but … every now and then they find it! Many large coal deposits - in the Donbass, the Dnieper basin, in eastern Germany - literally sit on salt domes. In the Permian time (and no one disputes this), the most powerful accumulation of rock salts in the geological history of the Earth took place. The following scheme is adopted: the drying heat, the water of the lagoons and bays evaporates, and the salts are precipitated from the brines, similar to what happens in Kara-Bogaz-Gol. Where can we get botanical splendor? And the coals nevertheless started!

It is still unclear how and under what conditions peat can be converted to coal. It is usually said that peat, slowly sinking into the depths of the Earth, successively falls into areas of increasing temperatures and pressures, where it is converted into coal: at relatively low temperatures - into brown, at higher temperatures - into stone and anthracite. However, experiments in autoclaves were unsuccessful: the peat was heated to: all kinds of temperatures, created different pressures, held under these conditions as long as desired, but no coal, even brown, could be obtained.

In this regard, different assumptions are made: the range of assumed temperatures for the formation of brown coal varies, de, with different duration of the process, from 20 to 300 ° C, and for anthracites from 190 to 600 ° C. However, it is known that when peat and its host rocks are heated to 300 ° C and higher, it would ultimately turn not into coal, but into completely special rocks - hornfels, which in reality does not exist, and all fossil coals are a mixture of substances, not wearing no traces of exposure to high temperatures. In addition, according to some quite trivial signs, it can be confidently asserted that the coals of many deposits have never been at great depths. As for the duration of the coal-forming process, it is known that the coals of the Moscow region, one of the oldest in the world, are still brown.and anthracites are found among many young deposits.

Another reason for doubt. Peat bogs, the ancestors of future coal basins, should arise on vast plains located far from the mountains, so that slowly flowing rivers could not carry fragments of rocks here (they are called terrigenous material). Otherwise, the peat will be silted up and pure coal will never come out of it. At the same time, a strictly stable tectonic regime is also required: the bottom of the bogs must submerge rather slowly and smoothly so that the released volume has time to be filled with organic matter.

However, the study of coal-bearing regions shows that coal deposits quite often arose in intermontane depressions and foothill troughs, near the front of growing mountains, in narrow slit valleys - in a word, in places where terrigenous material accumulates very intensively, and where peat bogs, therefore, can be not only silted up, but also completely destroyed by stormy mountain streams. It is in such unsuitable (according to theory) conditions that thick coal seams are encountered, reaching 50-80 m.