People have been trying to understand the meaning of their dreams ever since history was recorded. And, probably, our ancestors did this even earlier, therefore it is not at all surprising that we continue to solve our dreams in an attempt to at least understand something.

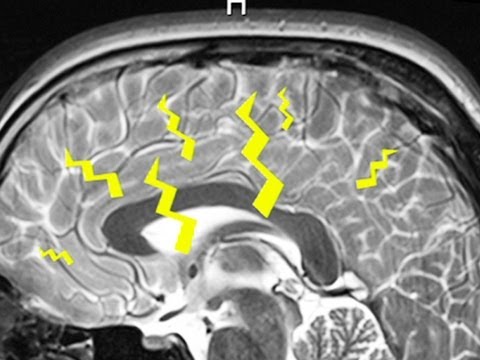

One of the most famous researchers in this area was Sigmund Freud, but today, thanks to modern technology, scientists have the ability to literally look into the brain to see what happens to us while we sleep.

Why do we dream

In 2004, scientists were able to explain where dreams come from in the brain by studying a patient with Charcot-von Willebrand syndrome, a rare condition that leads, among other things, to disrupted sleep cycles and loss of the ability to dream. Scientific American reports that the researchers were able to find a person who does not have severe symptoms, but remains dreamless.

During the experiments, it turned out that the girl had a damaged part of the brain associated with emotions and visual memories. This allowed scientists to assume that this particular area of the brain is associated with the generation or transmission of dreams.

Medical Daily cites data from a 2011 study in which a team of Italian scientists measured electrical brain waves and concluded that the reason people remember dreams better is the lower frequencies of waves in the frontal lobes when they wake up. This suggests that the mechanisms for remembering dreams and real events are almost the same.

Promotional video:

What dreams can tell about us

Dream books often try to interpret events or images that we see, but these descriptions are relative and unscientific. However, it cannot be said that dreams mean absolutely nothing. Sleep is an indicator of what a person is thinking about. A DreamsCloud survey showed that people with higher levels of education are more likely to dream about work or school-related situations, and, in addition, they often dream of work colleagues, as opposed to less educated people.

“We dream of what worries us the most,” Angel Morgan, MD, explains to The Huffington Post. In other words, the dreams of an educated person are more complex and always full of events, since there are likely more problems in his life that need to be solved.

Some research data suggest that people who have lucid dreams (that is, they understand that this is a dream and can even control it) are more effective in solving everyday tasks.

According to Live Science, dreams can also talk about our mental state. Researchers from the Central Institute of Mental Health in Germany have shown that people who commit murder in their sleep are more often introverts in life, but rather aggressive. Business Insider reports that people prone to schizophrenia talk about their dreams in few words, while people with bipolar disorder talk a lot and in confusion.

Why are dreams needed

Sigmund Freud argued that dreams are manifestations of repressed desires, and today a number of experts hold the same opinion. Others suggest that dreams don't exist at all. This theory, also known as the activation and synthesis hypothesis, proposes to perceive dreams as brain impulses that "pull" random thoughts and images from our memories, and people build a dream out of them after awakening.

But most experts agree that dreams have a purpose, and that purpose has to do with emotions. “Most likely, dreams help us process emotions by encoding them. What we see and experience in our dreams does not have to be real, but the emotions associated with these experiences are certainly real, writes Sander van der Linden, professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science (London School of Economics and Political Science), in its Scientific American column.

Simply put, dreams try to rid us of unpleasant or unnecessary emotions by tying them to the experience in the dream. Thus, the emotion itself becomes inactive and ceases to bother us.