"Geronimo!" - with such a cry American airborne paratroopers jump from the plane. The tradition owes its origin to the Apache leader Geronimo (1829-1909), whose name inspired such fear on the white settlers that as soon as someone shouted “Geronimo!” Everyone jumped out the windows.

Here are the details …

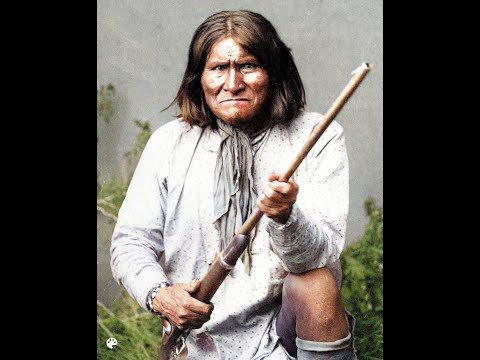

“Never before has nature carved such terrible features,” one journalist wrote about Geronimo in 1886, “a weighty, wide nose, a low wrinkled forehead, a powerful chin and eyes - two pieces of black obsidian, as if illuminated from within. But the most remarkable feature was the mouth - sharp, straight, thin-lipped, like a cut, without any bends that could soften it."

Even today, one cannot be indifferent to the last great Indian leader who resisted the inevitable wave of the American state's seizure of lands in the west.

By 1881, the Cheyenne and Sioux, who had destroyed Caster's army at Little Bighorn, had already been defeated and pacified. Crazy Horse - stabbed to death with a soldier's bayonet while resisting arrest. Sitting Bull - a prisoner at Fort Randle - was interviewed by newspapers. Joseph, the chief of Nez-Perce, surrendered and his people died of malaria in Oklahoma.

Only four squads of Chiricahua Apaches remained at large in southern Arizona and New Mexico. Chiricahua had many glorious chiefs such as Cochise, Mangas Coloradas, Delgadito, and Victorio. By 1881, they were all dead. Nevertheless, for five years after that, another popular warrior, Geronimo, led this incredible confrontation. In the end, 16 soldiers, 12 women and 6 children remained in the detachment of Geronimo. They deployed 5,000 US troops (or a quarter of the entire US army) and possibly 3,000 Mexican soldiers against them.

Because of this difference and the fact that Geronimo held out the longest, he became the most famous of the Apaches.

Promotional video:

Goyatlai (Geronimo) was born in the Apache settlement of Bedoncohe, located near the Gila River, in the territory of modern Arizona, at that time - in the possession of Mexico, but the Geronimo family always considered this land theirs. This bend in rivers lies in the heart of the Gila (Jila) Desert, close to those cliffs under which the Mogollon culture lived in the 13th century. Apaches often camped at these places.

Geronimo's parents trained him according to the Apache tradition. He married a Chirikauhua Apache woman and had three children. On March 5, 1851, a detachment of 400 Mexican soldiers from the state of Sonora, led by Colonel José Maria Carrasco, attacked Geronimo's camp near Chanos while most of the men of the tribe went to the city to trade. Among those killed were Geronimo's wife, children and mother.

The leader of the tribe, Mangas Coloradas, decided to take revenge on the Mexicans and sent Goyatlai to Kochis for help. Although, according to Geronimo himself, he was never the leader of the tribe, from that moment he became its military leader. For the Chirikauhua tribe, this also meant that he was also a spiritual leader. In accordance with his position, it was Geronimo who led many raids against Mexicans, and subsequently against the US Army.

Geronimo was not a leader, but rather a visionary shaman and a leader in battle. The leaders turned to him for the wisdom that came to him in visions. Geronimo did not have the nobility and stoicism of Cochise. Instead, he knew how to manipulate and choose the best case. He constantly made plans, fearing the unknown, and worried when something was out of his control. He did not trust anyone, and this mistrust was increased by Mexican and American traitors. He was very curious and often pondered things that he could not comprehend. At the same time, he possessed pragmatism.

Geronimo had a gift for oratory, but it was not in eloquence, but in the ability to argue, lead a discussion, and carefully weigh an idea. With a revolver or with a gun, this was one of Chiricahua's finest shooters. He liked to drink well - it was Tisvin - Apache corn beer, or whiskey from merchants. Throughout his long life, Geronimo had 9 wives and countless children.

What helped Geronimo become a leader? His fearlessness in battle, his foresight of events and his sharp mind - that is what made people respect his word.

There were few Apaches - about 6000-8000 by 1860. And although whites called everyone Apaches, they were many separate groups, often hostile to each other. And of course, the success of the army in pacifying most of them was ensured just by setting one tribe against another.

His family name was Goyakla, which is most often translated as "Yawning". Geronimo was named by the Mexicans, probably after Saint Jerome. The name came to him in battle, when Goyakla ran through a hail of bullets several times to kill an enemy with his knife. Seeing an Indian warrior, the soldiers in despair called on their saint.

The turning point in Geronimo's life took place in northern Chiricahua, in the town of Janos. Today Janos is just a truck stop 35 miles south of New Mexico, but then it was an important stronghold for the Spanish. By the early 1850s, when only a few of the Chiricahua had seen the White Eyes (as they called the Anglo-Americans), they had already experienced two centuries of bloodshed with the Spanish and Mexicans.

The latter, having lost hope of achieving a stable peace with the Apaches, began genocide, in 1837 promising a government reward for the Apache scalps in Chihuahua.

Around 1850, the inhabitants of Janos offered peaceful trade to the Chirikahua Apaches. While the men traded skins and furs in the city, women and children camped nearby. But one day a passing Mexican platoon from the neighboring state of Sonora attacked the camp. 25 women and children were killed, and about 60 people were taken into slavery.

Geronimo returned from the city to find the dead bodies of his mother, young wife and three children. "There were no lights in the camp, so I quietly returned unnoticed and stopped by the river," he said more than half a century later, "how long I stood there, I don't know …"

Geronimo's wife and child.

In the middle of the night, the Apaches retreated north, leaving their dead. “I stood until all of them passed me by, hardly realizing what I had to do, I had no weapons, I had no great desire to fight, I didn’t want to find the bodies of my loved ones, since it was forbidden (the leader, for security reasons). I didn't pray, didn't decide what to do, because now I just didn't have any goal. In the end, I silently followed my tribe, keeping so far away from them so that I could only hear the soft stamping of the Apaches leaving.

Until the end of his life, Geronimo hated Mexicans. He killed them wherever he met, without any pity. Although this number is not credible, the Governor of Sonora claimed in 1886 that in just five months, Geronimo's gang had killed between 500 and 600 Mexicans.

Shortly after fleeing Janos, the moment came when Geronimo received his Power. One Apache, who was still a boy at the time, said: Geronimo sat alone, grieving for his family, sitting with his head bowed and crying when he heard a voice calling his name 4 times, a sacred number for the Apaches. Then he received a message: “No gun can kill you, I will take out the bullets from the Mexican guns, and only gunpowder will remain in them. And I will direct your arrows. From that day on, Geronimo believed that he was invulnerable to bullets, and this was the basis of his courage in battle.

In the 1850s, the White Eyes began to advance through the Chiricahua land. At first, the Apaches hoped to be able to live in peace with the trespassers of their borders. Cochise even allowed crews to be sent from Butterfield Station via the Apache Pass, where the life-giving spring was.

But in February 1861, hothead Lieutenant George Bascom, a West Point novice, called Cochise to his camp near the Apache Pass to accuse the chief of stealing a bowler hat and stealing a 12-year-old boy from a ranch 80 miles away. Cochiz denied these accusations, but Bascom, having surrounded his tent with soldiers in advance, announced that he would keep Cochiz captive until he returned the vessel and the boy.

Cochise immediately pulled out his knife, cut through the tent and broke free through the barrage of fire. Bascom captured six who accompanied Cochiz - his wife, two children, a brother and two nephews. For the exchange, Cochiz captured several whites, but the negotiations failed, then he killed and mutilated his victims. Later, US troops captured several more male relatives of Cochiz. This treatment of the chief Chiricahua rebuilt the Apaches against the White-Eyed as much as it had against the Mexicans decades before.

The following year, soldiers seized a vital spring at the Apache Pass and established Fort Bowie there, from where the campaign against Chiricahua began. Now the ruins of the fort are preserved as a historical monument. When I visited it, I saw crumbling adobe walls, recently covered with a protective composition, which made them strangely prehistoric. The old cemetery next to the fort is overgrown with mesquite and grass, but the source still springs from a dark crack.

Over the next ten years, the federal government became firmly convinced that reservations were the best solution to the "Indian question." In 1872, the Chiricahua Reservation in southeastern Arizona was established. The site for her was well chosen, as it lay right in the center of the Indian homeland. The agent, Tom Jeffords, a former stationmaster, was distinguished by his sympathy for the Apaches and was the only white man with whom Cochise had friendly feelings. Four years later, the government felt that the Apaches had too much freedom, Jeffords was fired, and the Indians were ordered to move to San Carlos, the former homeland of the Western Apaches, who were once their enemies. This place was considered by the bureaucrats of Washington to be good for the life of the Indians.

The new agent was John Clum. Only 24 years old, he was honest and brave, but at the same time smug and domineering (for this bombast, the Apaches called him a turkey). Clum traveled to Fort Bowie, where he managed to convince about a third of Chiricahua to move to San Carlos, but Geronimo escaped at night, taking with him about 700 men, soldiers, women and children who refused to give up their freedom.

General George Crook, a wise and humane officer, realized that the Apaches were too elusive and too independent to be completely disarmed by the American army. Instead, he proposed a compromise: Apaches had to wear brass tags and be marked daily, and at the same time, receive state rations, but at the same time they were allowed to more or less freely choose places for parking and hunting. Thus, leaving the reservation was not that difficult. But the people of Arizona pleaded that "these traitors", who were pampered and fed during the barren winters, would repay with robbery and murder in the summer. The world was not easy.

In the spring of 1877, Klam traveled to Ojo Caliente, New Mexico, to ferry the Warm Springs Apaches, the Cochise Chiricahua's closest allies, to San Carlos. For centuries, the Hot Springs Apaches have considered Ojo Caliente a sacred place. The V-shaped crevice, which its waters cut through the hills, was a natural fortress. And around - an abundance of wild fruits, nuts and various animals.

Learning that Geronimo was in those places, Klam sent a messenger to him with a proposal to negotiate. Meanwhile, he got a job at the Hot Springs agency, hiding 80 soldiers in a warehouse. Geronimo arrived on horseback with a group of Chiricahua warriors.

Geronimo (right) and his warriors.

Klam left notes of this ambush and mentioned it in his memoirs. On a sunny May day, holding copies of these notes, I wandered through the ruins, trying to reconstruct the events.

Here, on the porch of the main building, as Klam wrote, stood a self-confident agent, his hand an inch from the grip of a Colt.45 caliber. And here Geronimo sat on a horse, behind him - a hundred Apaches, and his thumb - an inch from the trigger of his Springfield rifle (50 caliber). They exchanged threats. At a signal from Klam, the doors of a warehouse 50 yards from here swung open and the soldiers surrounded Chiricahua. 23 rifles were aimed at the leader, the rest at his people, but Geronimo did not try to raise his rifle. He gave up.

Clum put him in iron shackles and brought him to San Carlos as part of a sad procession of Chiricahua prisoners, among whom a smallpox epidemic broke out. For two months Geronimo was held in shackles, intending to kill him. Hanging the Apache chief was Klam's dream, but he could not get permission from the authorities in Tucson. In the end, in a fit of fervor, Klam resigned and his successor freed Geronimo.

In his memoirs, Klam was jubilant: "Thus ended the first and only real capture of the CHERONIMO." But both Bascom's public insult to Cochiza and Klam's treatment of Geronimo had far-reaching consequences.

For the next four years, Geronimo, who was already in his 50s, which is already old age for the Apaches, enjoyed relative freedom on the reservation. He could leave the reservation whenever he wanted. Sometimes the warrior even felt that he could get along with the White-Eyed, but soon he was disappointed in this.

At this time, Geronimo traveled all over his homeland. The mountains were a natural landscape for the Apaches; among the rocks and gorges, they felt invulnerable. The Spirits of the Mountains, divine beings who healed and protected Chiricahua from enemies, also lived here.

In the 50s - the years of Geronimo's youth - Chiricahua traveled through the land that their god Ussen gave them. This area included Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and vast lands in northern Mexico along the Sierra Madre. Army officers who happened to transport Indians across this desert called it the most difficult terrain in North America. Lack of water, steep and tangled mountain ranges, cacti and thorny bushes tearing clothes, rattlesnakes underfoot - the whites hardly dared to go there.

But the Apaches have mastered this area. They knew every stream and spring for hundreds of miles around, it cost them nothing to ride a horse and even run 75-100 miles in a day, they could climb rocks where white soldiers stumbled and fell. They could become invisible in the middle of the sparse bush plain. And they traveled in such a way that no one could distinguish their tracks, except that another Apache. In the desert, where the whites were starving, they thrived - mesquite beans, agave, saguaro fruits, and chollas, juniper berries, pinon nuts.

In the 1880s, when there were much more White-eyed, Geronimo and his people crossed the border into the Sierra Madre mountains, where the Chiricahua felt completely safe. It was here, far in the mountains, that Juh, a friend of Geronimo and one of Chiricahua's best military strategists, received a vision sent by Ussen. Thousands of soldiers in blue uniform emerged from the blue cloud and were lost in a deep crevice. His warriors saw this vision too. The shaman explained it this way: “Ussen warns us that we will be defeated, and perhaps all of us will be killed by the troops of the government. Their strength is in their number, in their weapons, and this power, of course, will make us … dead. Ultimately, they will destroy our people."

Determined to finally crush Geronimo's gang, General Crook in May 1883 launched one of the most desperate campaigns ever waged by the US Army. With 327 people - more than half of them were scouts from other Apache tribes - Crook went deep into the Sierra Madre, his guide was the Apache of the White Mountains, who at one time traveled with Geronimo.

Geronimo himself was far from there - in the east, in Chihuahua, catching Mexicans in order to exchange them for prisoners of Chiricahua. Jason Betzinez, a young Apache at the time, recounted how Geronimo unexpectedly dropped his knife one night at dinner. His Power spoke to him, sometimes in unexpected flashes.

“Guys,” he gasped, “our people, whom we left in the camp, are now in the hands of American troops. What do we do now? And indeed, just at this time, Crook's vanguard, consisting of the Apaches, attacked the Chirikahua camp, 8-10 old people and women were killed and 5 children were taken prisoner.

Geronimo's group hurried back to their fortification, where they saw Crook with the little captives. Other groups joined them, and for several days the Chiricahua camped on the nearby cliffs, watching the invaders.

Crook's invasion of the Apache stronghold was a big blow to them. What happened next in the Sierra Madre is still not known for sure. Indeed, despite the significant forces that Crook gathered, the Apaches outnumbered them, in addition, the soldiers ran out of food supplies, all this made them very vulnerable.

After waiting five days, Geronimo and his men, disguised as friends, infiltrated the Apaches from the Kruk camp. They joked and had fun with the White Mountains scouts. The Chiricahua then began a victory dance and invited the scouts to dance with the Chiricahua women. Geronimo's plan was to surround the dancing scouts and shoot them. But the scout chief appointed by Crook, an old highlander named Al Sieber, forbade the Indians to dance with the Chiricahua, either out of principle or because he had sniffed out something.

So, the ambush fell through, and Geronimo, along with other ringleaders, agreed to negotiate with Crook. Then part of Chiricahua headed north, accompanied by soldiers, to San Carlos. Others have promised to do so when they gather their people. Geronimo remained at large for another 9 months, but in late winter he joined them.

In November 1989, a friend and I tried to find the spot in the headwaters of the Bavispe River where the general and Geronimo met. On the fifth day, guided by the map drawn by Crook, we reached the remote bank of the river, which corresponded to the description, and climbed to the top of the Mesa - perhaps this was the Chirikahua camp.

I was struck by the beauty of the Sierra Madre: hills covered with lush grass, scattered here and there oaks and junipers, giving way, as we climbed, pine (ponderosa pine), and in the distance - a blue ribbon of Bavispa, surrounded by bushes, branching from him canyons disappearing into labyrinths of rocks.

James Kaywaykla, Apache of Hot Springs, was a boy in the 1880s and stood in this camp. Seventy years later, he recalled: “In this place we lived for several weeks, lived as if we were in heaven. We hunted again, held holidays, danced by the fire … This was the first time in my memory when we lived the same way as all the Apaches lived before the arrival of the White-eyed."

Crook's defiant attack on the Sierra Madre camp influenced the course of the war more than other White actions. Most of the Apaches were demoralized, they no longer tried to escape from the reservation. In negotiations with Crook, Geronimo insisted that he always wanted to live in peace with the White-Eyed. Now, in 1884, he made a sincere attempt to do so. With several other groups under the vigilant supervision of Lieutenant Britton Davis, he settled at Turkey Creek on the White Mountains Reservation.

Turkey Creek at first seemed to have a benevolent and enlightened leadership on both sides. The government decided that Chiricahua should become farmers, and most Apaches were ready to try the new occupation. But even the Indians themselves did not understand what violence they committed against their way of life, turning them from nomads into farmers.

Geronimo insisted that they would only live on the reservation for a year, while the entire Southwest thanked God that the war with the Apaches was finally over. But tensions on Turkey Creek grew. The government banned two favorite Apache activities: brewing Apache beer - tisvin, followed, of course, by drinking, and beating wives. Events culminated in May 1885. Several of the chiefs went into a big booze, and the next day they appeared before Davis, challenging him to put them in prison. At the same time, Geronimo, for some reason, was informed that Davis was going to arrest and hang him.

On May 17, Geronimo left the reservation, taking with him 145 Chiricahua men, women and children.

The story of Geronimo's last 15 months on the loose takes on epic proportions. While US soldiers vainly caught Apaches throughout the Southwest, newspapers in Arizona and New Mexico went into hysterics: "Geronimo and His Assassination Gang Are Free Now," "The Blood of Innocent Victims Calls to Heaven for Vengeance." During their first throw into Mexico alone, the fugitives took their lives 17 White-eyed. Often their victims were found disfigured. It was rumored that Geronimo sometimes killed babies by throwing them into the air and catching them with his knife.

American soldiers, however, also killed children, guided by the reasoning that "lice will grow out of nits." And in 1863, after killing the great Apache leader Mangas Coloradas, they cut off his head and boiled it. According to Apache ideas, a person was doomed to live in the next world in the same condition as he died, so the White-Eyed deserved the same treatment for killing and maiming the Indians.

Moreover, preparing for battles, the Apache boys went through exhausting trials, hurting themselves, learned not to be afraid of death. Therefore, the most cruel punishment that Apache could imagine was prison, and it was she who waited for the Indians who fell to the White-Eyed.

In the last years of his freedom, Geronimo killed settlers and ranch workers mainly in order to obtain ammunition, food and horses, it was just the easiest way for him. The terrible torture he sometimes resorted to was the price to pay for what was done to his mother, first wife and three children. Although decades later, in old age, Geronimo woke up in horror at night, regretting that he had killed small children.

***

The army pursued Geronimo's gang, and the fugitives divided into small groups and fled. Platoon after platoon stubbornly followed them only in order to finally lose their tracks in the rocks and canyons. Finally, in a coordinated strike, several columns of soldiers had already decided that they had cornered Geronimo in Mexico, but at that moment he happily returned to the United States, rode to the White Mountains reservation, stole one of his wives, a three-year-old daughter and another woman there. from under the nose of the patrol and disappeared without leaving a trace.

However, the Chiricahua were also tired of the fugitive life. A few weeks later, one of the most cruel leaders, Nana, by then already an 80-year-old lame old man, agreed to return to the reservation with several women, among whom was one of Geronimo's wives. In March, Geronimo, intent on surrendering, met Crook at the Canon de los Embudos just south of the border. For two days of negotiations, Geronimo made dozens of claims.

“I think I'm a good person,” he told Crook on the first day, “but newspapers all over the world say I'm bad. It's not good to talk about me like that. I have never done evil without a reason. One God looks at all of us. We are all children of one God. And now God is listening to me. Sun and darkness, winds - they all listen to what we are saying now."

Crook was relentless. “You yourself must decide whether you will stay on the warpath or surrender without setting conditions for us. But if you stay, I will follow you until I kill the last of you, even if it takes 50 years."

The next day, softening, Geronimo shook hands with Crook and uttered his most famous words: “Do with me what you want. I give up. Once I was fast as the wind. Now I give up, that's all."

But that was not all. Crook headed for Fort Bowie, leaving the lieutenant behind to escort the still armed Apache warriors. That night, a liquor dealer who sold whiskey to the Indians told Geronimo that he would be hanged as soon as they crossed the border. The Indians, still drunk in the morning, moved only a few miles north, and at night, when Geronimo's compass of confidence turned back again, he fled south, a small group of Apaches followed him.

Thus began the last stage of the Chiricahua confrontation. Exhausted and fed up with Washington's criticism, General Crook resigned. He was succeeded by Nelson A. Miles, a vainglorious presidential man who made a name for himself in the history of fighting Sioux and Nez Perce. But his five-month effort to capture the last 34 Chiricahua was unsuccessful.

By the end of August 1886, the fugitives were desperate to see their families again. They sent two women to a Mexican city to see if they could surrender. Shortly thereafter, the brave Lieutenant Charles Gatewood rode with two Apache scouts to Camp Geronimo on the Bavisp River. Gatewood played a trump card by telling Geronimo that his men had already been sent by train to Florida. The news stunned them.

On September 4, 1886, Geronimo met Miles at Skeleton Canyon in Peloncillos, west of the Arizona-New Mexico border. “This is the fourth time that I have surrendered,” said the warrior. “And I think the last one,” the general replied.

Nicknamed the Tiger in Human Form in the newspapers, Geronimo made a small fortune with his public appearances when he was already captured by whites. At the 1905 exhibition, thousands of people crowded the stands to watch Geronimo (pictured wearing a top hat) representing the "last bison hunt" by car.

No one guessed that Geronimo was not a prairie Indian, that he had never hunted buffalo and did not wear a sun hat. He also did a very lively business of photographs, bows and arrows. "The old gentleman is quite highly regarded," the audience remarked, "but Geronimo is the only one."

Geronimo gave up, hoping to be reunited with his family in five days, hoping that his "sins" would be forgiven and his people could finally settle on a reservation in Arizona. But Miles lied. Few of them could see their homeland again.

After Geronimo's surrender in 1886, he and his men, now captives, were quickly evacuated from the state of Arizona, whose inhabitants were eager for revenge. "It was a matter of honor for us," wrote General Nelson Miles, "to prevent them from forming a gang again." At every stop on the road from Texas to Fort Pickens in Florida (pictured), crowds of whites gathered to gaze at the captive Apaches.

For their intransigence, Chiricahua were punished like no other Indians in the United States. All of them, even women and children, ended up working as prisoners of war for about 30 years, first in Florida, then in Alabama and finally at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. In 1913, the Chiricahua were assigned a seat on the Mescalero Reservation in southern New Mexico. About two thirds of the survivors moved to Mescalero land, one third remained at Fort Sill. Their descendants now live in these two places.

The old warrior spent his last days signing autographs and farming at Fort Sill. But one of the visitors saw a completely different Geronimo. Lifting his shirt up, he bared about 50 bullet wounds. Putting a stone into the wound, he made the sound of a shot, then threw the stone and shouted: "Bullets cannot kill me!"

Last spring, I spent a day on the Mescalero Reservation with Ouida Miller, Geronimo's great-granddaughter. A pretty woman 66 years old with a gentle character, she kept the memory of the great warrior all her life. “We still get hate letters from Arizona,” she says. "They say their great-grandfather was killed by Geronimo."

Geronimo's relatives can be found among Mescalero, New Mexico, where most of the Chiricahua settled after the liberation of their Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Geronimo's spirit lives on in his great-grandson Robert Geronimo, who had to go through many scandals and fights, defending his name. “Everyone wants to brag that he beat Geronimo,” says the 61-year-old former rodeo cowboy. "I think I'm going on his way."

His sister Ouida Miller still receives angry letters about his famous grandfather, whose loyalty and love for his family are little known traits of his character. “I'm sorry I didn't know him,” she says.

In 1905, Geronimo approached President Theodore Roosevelt with a request to transfer his people back to Arizona. “This is my land,” he wrote, “my home, the land of my fathers, to which I ask permission to return. I want to spend my last days there and be buried among those mountains. If this could happen, I would die in peace, knowing that my people will live in their homeland, that they will increase in number, and not decrease, as they do now, and that our family will not disappear."

President Roosevelt rejected this request on the pretext that Apaches are still very badly treated in Arizona. "That's all I can say, Geronimo, except that I am very sorry and I have nothing against you."

Geronimo's fears that his people would die out was not just a beautiful phrase. During their heyday, Chiricahua numbered no more than 1200 people. By the time they were released, that number had dropped to 265. Today, thanks to the dispersal over the following decades and the inter-tribal marriages of Chiricahua, it is impossible to count accurately.

Last fall I visited the site of the last Indian surrender at Skeleton Canyon. It is located in a quiet forest clearing at the confluence of two streams. Tall sycamores obscure the place where Miles placed the commemorative stones, symbolically moving them from their former places to show the Apaches what the future holds for them.

Only 3-4 ranches are located within 15 miles of Skeleton Canyon. From the place of surrender, I climbed for a long time into the mountains up the stream, bypassing its idyllic bends. And all day I saw no one. Not for the first time, I wondered how in this vacant splendor it was not possible to find a place for less than 1000 people - the population of small Arizona towns like Duncan or Morency.

According to those who lived with Geronimo, the rest of his life he bitterly regretted that he had surrendered to Miles. Instead, he wished to remain in the Sierra Madre with his warriors, fighting to the last man.

On a winter night in 1909, returning home from the town of Lawton, Oklahoma, Geronimo fell from his horse and lay in a ditch until morning. Already an 85-year-old man, he died of pneumonia 4 days later. As he died, he remembered the names of those soldiers who remained faithful to him to the end.

Apache Cemetery at Fort Sill, in a quiet location by a tributary of the Cache Creek, has about 300 graves. In the center - Geronimo's grave - a pyramid of granite stones with an eagle carved from stone on top. The eagle's head, which had been knocked off by vandals, was replaced with a rough concrete replica. From it there are even rows of white gravestones. Each has a number in the back such as "SW5055" - the number that was on the copper cards of the Indians in San Carlos.