Sometimes advice not to drink raw water can be really helpful and keep infection away. However, according to scientists from the University of Arizona and Drexel University, this warning should probably be expanded with a recommendation to try to also "not inhale water particles." In a recently published paper, a group of researchers is investigating how splashing water in bathrooms and toilets can expose us to the bacteria that have caused most waterborne disease outbreaks in the United States.

“Many people in the United States believe that water quality problems are being successfully resolved and drinking water should no longer be a concern. However, the recent crisis in Flint, Michigan (where drinking water was contaminated with lead) and frequent outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease in the country suggest that this is not the case,”said Kerry Hamilton, assistant professor at the Fulton School of Engineering at Arizona State University. Earlier at Drexel University, Hamilton conducted research on how the bacteria Legionella pneumophila can grow and multiply in household water systems.

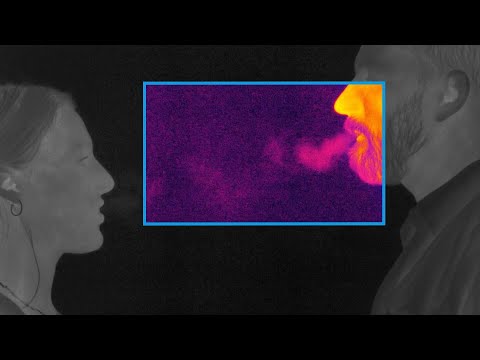

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Legionella bacteria, which cause Legionnaires' pneumonia-like disease, are responsible for a number of recent epidemic outbreaks. It can be fatal in 10-25 percent of cases and is considered one of the deadliest waterborne diseases in the United States. Infection occurs by inhalation and aspiration. This means that in order to accurately understand the conditions that can increase the risk of infection, researchers need to study the places where people can inhale water dispersed in the air.

“To protect people from infection, you first need to assess the risks,” explained Hamilton. “If we can better model and predict how water quality degrades under different circumstances, we can better prevent disease outbreaks.”

The study looked at multiple factors to assess the risk of disease. Numerous combinations of shower frequency, sink use and toilet flush have been studied; the scientists used the available data on the volume, size and dispersion of aerosol particles for various models of showers, mixers and toilets. Water with different concentrations of bacteria was used. It also took into account the fact that people who are old or already have health problems are at greater risk of getting sick from exposure to Legionella. It should be noted that this is one of the first studies in which the possible impact on the problem of water-saving technologies used, for example, in "green" buildings, is considered in detail.

“We found that bathing in the shower poses the greatest risk, probably due to the amount of time a person spends in the splashing water. With an equal concentration of bacteria, the risk of disease tends to be slightly lower with water-saving devices because they generate fewer respirable aerosol particles due to weaker or better dispersion of the spray,”commented Charles Haas, professor of environmental engineering at Drexel College of Technology, one from the co-authors of the article.

“Modeling different concentrations of Legionella in conventional homes and buildings that use water-efficient technologies remains a gap that our work is striving to fill,” the scientist added.

As might be expected, the risk of disease was higher with exposure from multiple sources, as well as for populations less able to fight infection.

Promotional video:

Most existing guidelines for measuring indoor water quality do not take into account disease risk assessment studies, but this does not mean that Legionella cannot enter the domestic water supply. For example, colonies of this bacterium can form in those homes where water sometimes stagnates for long periods of time (for example, in buildings intended for seasonal use).

Although it is Legionella pneumophila that has been studied, the results of the study provide a basis for assessing the risk of exposure to any bacteria lurking in domestic water supplies. In this way, the work can be used more broadly to make recommendations for “acceptable levels” of bacteria in building water systems. The work aims to improve methods for monitoring water quality in homes and can be used in conjunction with other regulatory approaches, Hamilton said.

Natalia Golovakha