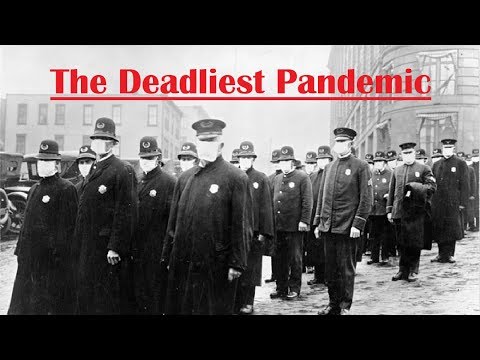

A century has passed since the Spanish flu claimed at least 100 million lives. And it is only a matter of time before a similar strain appears. A hundred years ago, the flu season was brewing in the most usual way. Most of those who fell ill in the spring recovered quickly, and the death rate was no higher than usual. The newspapers wrote more news about the war than about the flu. But in the fall, everything changed. The previously unknown virus turned out to be an extremely dangerous strain that wipes out populations in North America and Europe, killing its victims in a matter of hours or days. In just four months, the Spanish flu, or “Spanish flu” as it is called today, has spread throughout the world and has penetrated even the most isolated societies. By the time the pandemic got to the next spring, 50 to 100 million people - about 5% of the world's population - were dead.

A century later, the 1918 pandemic seems as distant from us a horror movie as the bubonic plague and other deadly diseases with which we have more or less conquered. But the flu is still with us - and it continues to claim between 250,000 and 500,000 lives annually. Each year brings a slightly different strain of seasonal flu, while a pandemic can occur depending on the assortment of influenza viruses in animals. In addition to 1918, there have been pandemics in the past century in 1957, 1968, 1977 and 2009.

Given the virus's tendency to mutate and its constant presence in nature (it appears naturally in wild waterfowl), experts are convinced that it is only a matter of time before a strain as contagious and deadly as the Spanish flu appears - and maybe even worse.

"Influenza pandemics are like earthquakes, hurricanes and tsunamis: they appear, some worse than others," said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research at the University of Minnesota. "It is foolish to believe that we will not have a second such event as in 1918."

But when it will take place, he continues, it is impossible to predict: "As far as we know, everything can start even now, as we speak." It is impossible to predict exactly how they will develop when the Spanish flu-like strain reappears and begins its bloody harvest. But we may well make some educated guesses.

First, the impact of the virus will depend on whether we catch it early enough to contain it, says Robert Webster of the Department of Infectious Diseases at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. There are many systems that are designed to do this: the World Health Organization's influenza surveillance team is constantly monitoring the development of the virus in six key laboratories around the world, and an additional set of agriculture-focused laboratories does the same for poultry and pigs.

“Our surveillance is likely to be as good as possible, but we can't track every bird and pig in the world - it's impossible,” Webster says. "We must be lucky if we want to contain the virus."

Promotional video:

The reality is, he continues, that the virus will almost certainly break out. Once that happens, it will spread across the globe in a matter of weeks, given the level of mobility today. “Influenza is one of those viruses that, if it enters a vulnerable population, grows rapidly,” says Gerardo Chowell, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Georgia State University. "Individuals already tolerate it until symptoms appear."

Since the number of people on the planet has more than quadrupled in the past hundred years, there are likely to be more infections and deaths compared to 1918. If 50 million people died as a result of influenza in 1918, today we could expect 200 million deaths. "That's a lot of body bags - they would run out very quickly."

As history shows, mortality is likely to be unevenly distributed among the populations of different countries. The Spanish flu has manifested itself in completely different ways in different countries. In India, for example, the virus killed more than 8% of the population, but in Denmark, less than 1%. Similarly, during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, deaths in Mexico exceeded those in France by 10 times.

Experts believe that a variety of factors influenced these differences, including prior population exposure to similar strains of influenza and the genetic vulnerability of certain ethnic groups (for example, Maori in New Zealand died seven times more often after contracting the 1918 flu than people on average around the world).

Poverty-related factors such as sanitation, basic health care and general health care also play an important role in the fight against the outbreak of the influenza virus, Chowell said. “In 2009, in Mexico, many people only went to the hospital when they got really, really bad, and it was often too late,” he says. Many of these sacrifices were due to an economic decision: going to the doctor meant losing a day of work, and therefore payment for that day. “I'm not saying this applies to every Mexican, but to the most vulnerable parts of the population for sure,” Chowell says.

If the pandemic affects the United States or other places without socialized medicine, similar socioeconomic patterns will apply to uninsured citizens. To avoid harsh medical bills, people without health insurance are likely to postpone hospital visits until the last moment - and then it may be too late. "We are already seeing this in other infectious diseases and access to health care."

Vaccines are the best cure for a pandemic, says Lone Simonsen, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Roskilde University in Denmark. But that requires identifying the virus, creating a vaccine and then distributing it around the world - easier said than done. Flu vaccines, which weren't available until the 1940s, are being made very quickly today, but they still take months. And even if we are successful in creating such a vaccine, it will not be possible to create enough doses for everyone, Osterholm says. “In six to nine months worldwide, only 1-2% of the population will have access to the vaccine,” he says. Another limitation, he adds, is that current flu vaccines are 60% effective at best.

Likewise, although we have medicines to fight the flu, we are not stockpiling them for a pandemic. “Today, we don't have enough antiviral drugs even in the richest country in the world, the United States,” says Chowell. "What can we expect for India, China or Mexico?"

In addition, the available drugs are also less effective than comparable treatments for other conditions, primarily because “the world treats seasonal flu as a fairly trivial disease,” Webster says. "It's only when there are major outbreaks like HIV that the scientific community begins to pay more attention to the disease."

Given these realities, hospitals will fill up very quickly, Osterholm says; medicines and vaccines will run out instantly. “We've already shocked the healthcare system here in the US with just one seasonal flu this year, and it wasn't even a particularly bad year,” he says. "This shows how limited our ability to respond to a large increase in the number of cases is."

As in 1918, as infections and deaths increase, cities around the world are likely to stall. Businesses and schools will close; public transport will stop working; electricity will go out; corpses will begin to accumulate on the streets. Food will be sorely lacking, as will the life-saving drugs that support the lives of millions of people with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, immunosuppressive conditions and other vital problems.

Even after the virus fizzles out on its own, the consequences of its appearance will be reflected for a long time in different parts of the planet. The 1918 virus was "terrible and then terrible," says Simonsen, that 95% of those killed were not very young and not very old, as is usually the case with the flu, but quite healthy, at the peak of their working capacity. The virus wiped out part of the workforce and had a profound impact on families, leaving numerous children orphans.

Almost reliably, scientists only found out about this in 2005, when they reconstructed the Spanish flu virus from samples taken during the Brevig mission in a village in Alaska, in which 72 of 80 residents were killed by the disease in less than a week. One victim's body survived in the permafrost well enough to allow a microbiologist to restore her lungs, which still harbored the genes of the virus.

Animal tests using the recovered viruses showed that the 1918 strain reproduced exceptionally well. It triggered a natural immune response, a cytokine storm, in which the body goes into overdrive, producing chemicals designed to prevent invasion. Cytokines are toxic on their own - they are responsible for pain and discomfort during the flu - and many of them can overload the body and cause general system failure.

Because adults have stronger immune systems than children and the elderly, scientists believe their stronger responses to influenza can be fatal. “We finally understood why the virus was so pathogenic,” Webster says. "The body was essentially killing itself."

In the decades following the Spanish flu, scientists have developed various immunomodulatory therapies that help mitigate cytokine storms. But this treatment can hardly be called ideal, and it is not available everywhere. “We are no better dealing with cytokine storms today than we were in 1918,” Osterholm says. "There are a few machines that can breathe and pump blood for you, but the overall outcome is very, very grim."

And this means that, just like in 1918, we are likely to see huge losses in life among young people and middle-aged people. And since life expectancy today is tens of years longer than it was a century ago, their deaths will be much more significant for the economy and society.

However, among the bad news, there is one chance of salvation: the universal flu vaccine. Significant resources have been devoted to this long-standing dream, and efforts to develop a breakthrough vaccine are gaining momentum. However, we can only wait and see if she arrives in time to prevent the next pandemic.

Ilya Khel