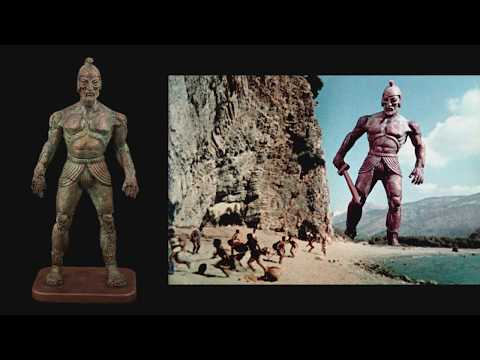

An automaton (automaton, from the Greek αὐτόματον - acting of its own free will), an automaton doll is an independently acting mechanism (or a set of mechanisms) that, with the help of an internal device, performs a certain set of actions according to a rigidly set program without direct human participation and imitates the shape and movements of a person, or animal.

Since ancient times, the myths of different peoples mention mechanisms that can be identified as automatons. Thus, Homer's Iliad tells how the god Hephaestus forged unusual tripods for serving guests:

And in the "Odyssey" are mentioned immortal dogs (gold and silver) which Hephaestus forged to guard the palace of the king of the Theacians Alkinoy. The myth of Daedalus says that he not only carved sculptures out of marble, but also made them move. The ancient Greek poet Pindar (522–442 BC) wrote about statues from the island of Rhodes, moving at the bewitching will of the Telkhin priests.

Promotional video:

In Jewish mythology, King Solomon built a throne with mechanical animals that greeted him as he sat on it - an eagle placed a crown on his head, a dove brought him a Torah scroll, and a golden bull and lion helped him ascend the throne. Numerous Chinese legends also tell about automatons.

Let's find out more about this all …

In the Middle Ages, similar stories can be found in the tales of The Thousand and One Nights, which mentions copper and iron statues animated by jinn.

However, it is also known about the real mechanisms built in ancient times. Even then, automatons were widely used for ritual purposes. So, for example, it is known that in Ancient Egypt the priests kept the statue of Osiris, in the eye sockets of which fire flashed at the right moment, and other temple statues had mechanical hands controlled by the priests. Herodotus mentions talking statues that stood at the gates of Egyptian temples, speaking the will of the gods. They could turn their heads, open their eyes, walk and … "at night they guarded the temples from robbers."

In ancient Greece, artificial people (automatons) were called androids, and their creators were called tavmaturges.

In the ancient world, automatons were used not only for ritual purposes, but also as toys and tools to demonstrate scientific principles, such as the mechanism built by the Greek mathematician Heron of Alexandria. Puppet dances were also arranged - the dolls were fixed on a large disk, which rotated under the pressure of a water jet, and they performed very intricate dances.

One of the oldest automatons about which there is reliable information is a mechanism made in the 4th century. BC e. Greek mathematician Archytus of Tarentum. It was a wooden pigeon flying "with the help of a secret spring and falling to the ground without the slightest difficulty."

The automaton maid is an invention of Philo of Byzantine, a mechanic of the 3rd century BC. e. This miracle of ancient Greek robotics was intended for a completely logical purpose - she filled a cup with wine, then mixed it with water. The supply of liquids came from two containers with tubes placed inside the mechanism.

In ancient China, automatons were made, set in motion by gunpowder explosions. There are also known Chinese dolls that tumble under the influence of mercury placed inside, which, by its fluidity, changes the center of gravity.

Lao Tzu mentions an automaton built for the emperor Mu Zhou (1023-957 BC) by the mechanic Yang Shi - a life-size mechanical "man". In the 5th century BC, the philosopher Mo-tzu wrote about his contemporary Lu Ban, who made artificial wooden birds that could fly.

In the middle of the 8th century, the first automatons were built in the palace complex of Baghdad, driven by the force of the wind. At the same time, Caliph al-Mukhtar amazed visitors to the Baghdad courtyard with a tree of gold and silver, in the crown of which a whole flock of mechanical birds sang in all voices.

In the 9th century, the Banu Musa brothers invented the flute-playing automaton, which they described in their book.

Ali ibn Khalaf al-Maradi wrote the Book of Secrets in the 11th century, a treatise entirely devoted to the construction of complex automatons. In it, he described the construction of thirty-one automatons.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Arab mechanic Abu al-Iz ibn Ismail ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari wrote a treatise "Kitab fi marifat al-hyal al-Khandasiyya" ("The book of knowledge about witty mechanical devices"). In this richly illustrated book, he described highly complex mechanisms - for example, a boat automaton with four mechanical musicians. It also described the elephant clock automaton, a replica of which can be seen today at the Ibn Batuta mall in Dubai.

Abu al-Iz ibn Ismail ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari Illustration in the "Book of knowledge about witty mechanical devices." Elephant clock, 1206

With some delay, automatons appeared in medieval Europe.

There is a legend that in the middle of the 13th century the Dominican monk Albert von Bolstedt from Cologne, nicknamed the Great by his contemporaries, made an iron maid who could walk, move her arms and even speak. According to another version of this legend, the automaton of Albertus Magnus was not a "servant" but a "talking head". However, the ending for both versions of the legend is sadly the same - Thomas Aquinas, a student of Albert, considered the automaton a devilish creation and smashed it with a hammer.

There is also a legend about a flying iron fly built by Albert W. Roger Bacon (1214-1294).

However, there is also quite reliable information about automatons built in Europe in the thirteenth century.

So the architect from Picardy Villars de Honnecourt, in his manuscript on architecture, written in the thirties of the thirteenth century, described zoomorphic structures of automatons, as well as an automaton-angel, which constantly turns to face the sun.

Jacques de Vaucanson. Automaton "Duck eating", 1739

And at the end of the thirteenth century, Robert II, Count of Artois, built an amusement garden in his castle, in which automatons - puppet monkeys, mechanical birds, mechanized fountains - were arranged for entertainment. The park was famous for its automatons as early as the fifteenth century, but was destroyed by English soldiers in the sixteenth century.

During the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Durer, Galileo Galilei, Juanelo Turriano were fond of the idea of creating automatons.

Leonardo da Vinci owns drawings of an automaton dating from around 1495. It was a human figure in medieval armor. Like many of Leonardo's other inventions, it was never built. However, in our time, Italian researchers have recreated da Vinci's plan using these drawings. This automaton can move its arms, turn its head, and sit down.

In 1560, the court mechanic of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V Juanelo Turriano made a mechanical monk. The automaton walked, crossed himself, raised the crucifix in his left hand, brought the cross to his lips and kissed it, moved his eyeballs and whispered silent prayers. The automaton moved on wheels hidden under a monk's attire. Today it is kept at the Smithsonian Institution in the United States. Another surviving automaton by J. Turriano - "The Lute Player" was sharpened by him even earlier in 1529.

In the seventeenth century, the art of making automatons spreads in France. In 1649, for the future King Louis XIV, who was then at a "tender age", artisans built an automaton, which consisted of several miniature courtiers, footmen and horses harnessed to carriages.

Musical automaton - Sharmanka. France, 1875

Many different automatons were created by German mechanics. Their action was based on the clockwork. Soon, similar mechanisms spread widely throughout the world. Thus, Father Sebastiano's “Italian” automaton was “like a moving picture, in terms of genre - an opera. The whole painting was 16 inches wide by 4 lines, 13 inches high by 4 lines and 1 inch thick."

Preserved evidence of the existence of automatons in pre-Petrine Russia. In particular, there is evidence that Ivan the Terrible had a mechanical automaton-servant - the "iron man". Merchant Johan Wem in his diaries gives the following information about him: “The iron man beat the tsar's bear for the amusement of the feasting on the tsar's bear, and the bear ran away from him in wounds and abrasions … in this unbearable Russian language, which never succumbed to me."

And Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich had a pair of mechanical lions on opposite sides of the throne in the Kolomna Palace, capable of copying some of the movements of real animals.

Further evidence of the existence of "Russian" automatons dates back to the Petrine and post-Petrine eras.

There is a legend that after the death of Peter the Great, his widow, Empress Catherine I, ordered to make the "Wax Person" - a mechanical doll that was an exact copy of the deceased. “Persona” had arms and legs moving with the help of special hinges, and on his head was a wig made from the hair of Peter I. The making of this automaton was allegedly entrusted to the Russian naturalist, scientist and statesman Yakov Bruce. However, this legend has very weak documentary evidence.

Automaton "Knight" recreated from a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci.

But it is known for sure that the Russian architect of Italian origin Giovanni Fontana created the “mechanical devil”.

In the 18th century, the French mechanics J. de Vaucanson and Pierre Dumoulin were famous for their automatons.

Mechanic and watchmaker Jacques de Vaucanson created the famous "Pied Piper" automaton. It was a "shepherd" who played the drum and flute (and had a very diverse repertoire). This automaton was introduced by the author of the French Academy of Sciences and was a great success. In 1738 Vaucanson built his second automaton, the Drummer, which played twenty different melodies on cymbals and drums. And in 1739 the inventor built an automaton known as the "Vaucanson duck" or "duck eating food." This mechanism was the first to be able to mimic food consumption.

Another eighteenth-century inventor, Friedrich von Knaus, created one of the first writing automatons.

Perhaps the most famous automaton creator in history was the Swiss watchmaker from La Chaux-de-Fonds Pierre Jacques Droz. Three of his masterpieces - "The Pianist", "The Artist" and "The Writer" aroused the surprise and admiration of his contemporaries. "The Pianist" - an automaton executed in the form of a woman playing the piano, consists of two and a half thousand parts. He not only played the piano - his eyes and hands moved, he “breathed” and even bowed at the end of each musical theme. The "Artist", which consisted of two thousand parts, depicted a child drawing while sitting at a table. He could do up to four drawings, and also imitated human behavior - moving his hands, eyes, and even blowing on paper to remove excess pencil powder. And finally, "The Writer" - the most complex of the three automata, consists of six thousand parts. This automaton could write a short text of up to forty words with a pen, and also very successfully imitated the behavior of a writer. All three automatons have survived and can be seen in the Museum of Art and History of Neuchâtel (Switzerland).

Here we examined in great detail the Robot of 250 years old and still working.

And in 1770, the inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen, who served at the court of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, invented a chess automaton for her - "Turk", which later became the hero of one of Hoffmann's phantasmagorias. For more than eighty years "Turok" beat almost all opponents, until it became clear that a live chess player was hiding under the chess table.

In the 18th century, the so-called automaton theaters became very popular, which are a kind of organ, supplemented by movable figures. A box, decorated like a palace hall, housed small porcelain musician dolls. After winding the springs, they began to move: the violinist moved his bow over a tiny violin, the harpsichordist lowered his hands to the keys of the instrument, the harpist played the strings of the harp. The spring activated not only the porcelain musicians, but also a musical mechanism hidden inside the box, which played several melodies.

Automatons were extremely popular in Japan and China in the 18th-19th centuries. In China in this era, automatic clocks were spread. And in Japan - karakuri automatons.

There are three types of such automatons: "Butai Karakuri", which were used in the theater; Zashiki Karakuri - for entertainment and Dashi Karakuri - used during religious holidays.

Karakuri Ningyo automaton. Japan, Second half of the 18th - 19th first half of the century.

In 1845, the Austrian émigré Joseph Faber exhibited in the United States the Amazing Talking Machine, which was a mechanical head that answered questions in a monotonous afterlife, in different languages (but with a German accent). The inventor himself controlled machine speech with the help of a keyboard instrument that made differently tuned metal plates vibrate. His next automaton, Euphonia, even sang.

In 1868, the American mechanic Zadok Dederic invented a "steam man" capable of "pulling a load in a cab like three horses harnessed to the same carriage."

In general, the period between 1860 and 1910 is considered the "golden age of automatons." In those years, many small, family-owned businesses that specialized in their manufacture flourished in Paris. So the production of mechanical dolls, which could walk, open and close eyes, was established by the watchmaker J. N. Steine.

In 1887, French watchmaker and jeweler Leopold Lambert founded a company in Paris for the production of musical automatic dolls. A year later, he received a gold medal at an exhibition in Barcelona, and in 1889 - in Paris. Many of his automatons today adorn the collection of French automaton dolls at the National Museum of Monaco.

French firms Vichy, Leopold Lambert, Fleischmann and Bledel were famous for their automaton dolls (the heads for their products were supplied mainly by German manufacturers).

A French illusionist (nicknamed the father of modern magic) who began his career as a watchmaker, Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin used automatons in his performances. The most famous of them are the singing "Bust of a Singer" (however, it was not an automaton who sang, but a live singer hidden behind the scenes) and "Palais Royal Confectionery" - a mechanical waiter who carries food and drinks around the hall.

But with the outbreak of the First World War, the production of automatons practically disappeared.

In the twentieth century, the era of a massive clockwork toy came to replace the cunning atomatons. As for the old automatons, they have taken their place in museums and private collections.

But in the same twentieth century, a special direction arose in the manufacture of automatons - animatronics. Animatronics is the design and manufacture of humanoid entertainment machines for the film industry and amusement parks. Walt Disney Pictures has been particularly successful in this.

But in the puppet theater, automatons are almost never used. The reason for this lies in the fact that in their work the role of the actor is minimized. Of the few cases of their use, one can perhaps recall only the performances "Three Fat Men" by Yu. Olesha (doll of the heir to Tutti) and "Nightingale" by G.-Kh. Andersen at the Obraztsov Puppet Theater in Moscow.

Viacheslav Karp