The description of the cave cities appeared in the writings of the first Russian travelers, who found the ancient cities and settlements already dead, their ground structures had by that time been erased by time.

The middle ridge of the Crimean mountains is much lower than the Main, and the mountains here look like frozen waves: one slope is gentle, the other is steep. This form is called "cuesta". On the flat tops of the cuestas, settlements began to emerge in the 4th-6th centuries, some of which later turned into fortresses. It was at this time that the first fortifications appeared on Mount Mangup. In later times, its majestic outlines gave rise to the Tatars' second name for the mountain - Baba-dag, translated into Russian - the Father of the Mountains. The Turkish traveler Evliye elebi wrote about Mangup in 1666: “This rock spreads like a flat plain … and around it gape abysses of a thousand yards - real abysses of hell! Allah created this rock to become a fortress …"

In the second half of the 6th century, a powerful fortress of Doros arose on Mangup. This border point of the Byzantine Empire was intended to protect the borders from the steppe nomads. At the end of the VIII century, when most of the Crimea was under the rule of the Khazar Kaganate, the Doros fortress turned into a hotbed of the anti-Khazar uprising - it was headed by Archbishop John of Gotha. However, the uprising was brutally suppressed, as evidenced by the layer of conflagration discovered by archaeologists.

In the 10th century, the Khazar Kaganate ceased to exist, and Mangup again became Byzantine. At this time, many local residents were engaged in viticulture and winemaking. On Mangup there are preserved grape press, carved into the rock. They are easily recognizable by two tanks connected by a groove: grapes were pounded in the larger tank, the wort was draining into the smaller one.

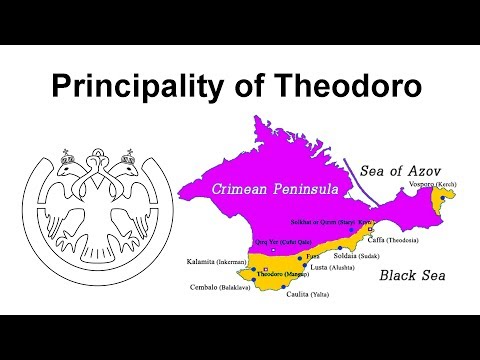

The brightest pages of the history of Mangup fell on the XIV-XV centuries. Then the plateau turned into the capital of the powerful principality of Theodoro, headed by immigrants from Byzantium - the Gavras dynasty. Until now, the ruins of the prince's castle and fragments of the fortress walls rise on Mangup.

The principality got its name by the name of Theodore Gavras. It is known that in the second half of the 11th century he ruled Trebizond (now it is the territory of Turkey), did not spare money to support monasteries, for some time lived as a hermit in the mountains, then led the struggle against the Seljuk Turks, was taken prisoner and executed when he refused to accept Mohammedanism. The Greek Church honors Theodore Gavras under the name of Saint Theodore Stratilates ("stratilate" means "voivode"). The nephew of Theodore Stratilates, Constantine Gavras, who fell into disgrace under the Byzantine emperor in the middle of the 12th century, was exiled to the Crimea. It was his descendants who united the lands around Mangup into the principality of Theodoro.

The principality, lying between the Tatar possessions (they occupied the steppe Crimea) and the Genoese colonies stretching along the southern and eastern coasts, became a stronghold of Crimean Orthodoxy. In the cliffs of the Mangup plateau, churches and cells of several monasteries were carved. One of them is located at the tip of the so-called Leaky Cape. (It really looks full of holes, since the opposite walls of one of the caves collapsed and a through hole was formed.) A staircase cut in the rock leads to a large room, from which entrances to small cells that have no windows are cut. Carving out this complex in the rock, the ancient builders carved a vertical pillar in a large room, the purpose of which is still unclear. However, tourists are attracted by the booming sound that fills the cave when struck.

Promotional video:

In the second half of the XIV century, the principality of Theodoro became a serious competitor for the Genoese in Mediterranean trade. In clear weather, the sea is visible from the top of Mangup in the west. There, in the Sevastopol Bay, was the port of the Theodorites, protected by the Kalamita fortress. Nearby, in Balaklava, there was the Cembalo fortress, which belonged to the Genoese. Such a confrontation is evidence of strained relations between neighbors.

The principality of Theodoro, reliably protected from its neighbors, the Tatars and Genoese, was unable to resist the Ottoman Turks who raided the Crimea in 1475. Having defeated all the fortresses, both the Theodorites and the Genoese, the Turks surrounded Mangup. The siege lasted several months without producing any results. Finally, the Ottoman warriors went for a trick: they imitated a retreat and thus lured Prince Alexander and his squad out of the city, and then suddenly attacked them. Pursuing the princely squad, the Turks captured Mangup, ravaged and burned the city. The principality of Theodoro turned into Kadylyk - a district of the Ottoman Empire.

CAVE MONASTERIES OF THEODORITES

On the territory of the Principality of Theodoro, in the cliffs of the cuestas, you can still see several cave monasteries today. For a long time, historians believed that their appearance was the result of the iconoclastic policy of the Byzantine emperor Leo III the Isaur: in 730 he declared the veneration of icons as idolatry. And then part of the monks who disagreed with the policy of the emperor took refuge in the Crimea from his persecution. However, recent archaeological research has shown that not all cave monasteries date back to the 8th century. The monasteries of Chelter-Koba, Shuldan and Chilter-Marmara appeared only in XIII. They did not have serious fortifications, and they were located near the roads, so that the monks, apparently, felt themselves masters of the situation here.

Perhaps it was the Shuldan Monastery that was one of the metropolitan's residences. A semicircular altar with a stepped bench has been preserved in the spacious cave church of the monastery. In the center of the altar, cut-outs for the throne are visible. Tombs are carved in front of the altar. A few years ago, only rare tourists and local boys visited the temple. In the summer of 2001, a flat stone appeared in the place of the throne, and in the niche for the image - small modern icons and a melted candle. Someone performed a service here …

In the rock on which the ruins of the Kalamita fortress rise, the caves of the Inkerman monastery are carved. Having gone through numerous periods of prosperity and decline, it is now operational. The resort visitors passing by it are struck by the church nestling against the rock and the balconies built into the cliff wall.

According to legend, the first cave temple in Inkerman was carved by the third bishop of Rome, Saint Clement, who was exiled to the Crimea in the 1st century for preaching Christianity. But in the Crimea, he gathered a small community and continued to preach. In 1634-1635, the priest Jacob, visiting the Crimean Khanate as part of the Russian embassy, described Inkerman as a place where Christianity flourished in antiquity. He said that the Russian ambassadors found the relics of the unknown saint here and wanted to transport them to Russia. The saint appeared to them in a dream and declared that he wanted to "continue to create Russia here."

After 150 years, Catherine II annexed Crimea to Russia.

ESKI-KERMEN

Not far from Mangup there is another large cave city - Eski-Kermen. Its first defensive walls were erected in the 6th century, simultaneously with the Mangup walls. This fortification housed a garrison recruited by the Byzantine authorities from local residents to protect the approaches to Chersonesos, a large port of the empire. Eski-Kermen was raided by nomads many times, he was also under the rule of the Khazar Kaganate. Now the entrance to the city looks open and unprotected, and once there was a fortress wall with three gates located one after another. A tower towered over the main gate. Despite the complexity and seeming perfection of the defensive system, it was destroyed in the early Middle Ages, possibly during the suppression of the anti-Khazar uprising. Now only cave casemates remind of the former inaccessibility of Eski-Kermen,stretching in a chain along the cliff.

But back to its best times. By the 12th century, Eski-Kermen had become a major trade and craft center. At that time, apparently, he also had great cultural significance - as evidenced by several cave temples. One of them is carved in a boulder that has broken away from the rock. In this temple, not only the altar was carefully carved, but also the sacristy, in which the ancient ministers of the cult kept the items necessary for the sacred rite. Today the temple bears the name "Three Horsemen" - after the fresco preserved inside.

In the central rider, striking a serpent with a spear, it is easy to recognize George the Victorious. There are only speculations about other warriors. Unfortunately, the right figure is now badly broken, and yet it is she who seems to be the most mysterious. Behind the back of the rider on the rump of a horse, an image of a boy was previously seen. The tombs cut into the floor, one of which is clearly for children, suggests that with George are depicted local saints who died during the defense of the city and were buried in the temple. According to another version, all three horsemen represent George the Victorious. Left warrior with a raised spear - the image of a reliable defender; right - George, saving from captivity a youth who asked for help in prayers.

The worship of holy warriors did not save the inhabitants of Eski-Kermen from the attack of the Tatars. In 1299, hordes of Nogai Temnik fell upon the Crimea. The city ceased to exist at a time when the principality of Theodoro was just gaining strength. For some time, life still glimmered on the plateau, but the raid of Emir Edigei in 1399 dealt the last blow to Eski-Kermen.

In 1578 Eski-Kermen was visited by the founder of Crimean studies Martin Bronevsky. The picture he saw already then differed little from the present one. Having examined the deserted plateau with the ruins of houses overgrown with bushes and the ruins of a basilica, Bronevsky noted: "… this place was once significant and important."

"AIR CITY" AND THE USPENSKY MONASTERY

Not only in the principality of Theodoro are cave cities located. The soft limestone of the Middle Ridge is perfect for creating cave structures, and the locals used it.

The most visited cave town of Chufut-kale nowadays by tourists lies on the outskirts of Bakhchisarai. It was inhabited 150 years ago. It was inhabited by the Karaites (or Karaites, Karai) - an ethnos formed from the descendants of the ancient indigenous population of Crimea (Cimmerians and Taurus) and the Khazars. The Karaites adopted the Jewish religion from the Khazar Kaganate, but they recognize only the Pentateuch of Moses (Torah) as sacred scripture and reject the Talmud. The language of the Karaites is close to the Crimean Tatar.

IM Muravyov-Apostol, traveling across the Crimea in the early 20s of the XIX century, admiring the Chufut-kale plateau rising to the heavens, called it an "air city". He wrote: “The dwellings of the Karaites are like eagles' nests on the top of a steep, inaccessible mountain … Chufut Karaites daily descend from their nests to Bakhchisarai, where they practice their crafts and trade all day long; and as soon as night falls, they return to their homes …”Now the Karaites are scattered throughout the Crimea. As a people, they are on the verge of extinction: there are about 800 of them left.

Chufut-kale is not like other cave cities - many above-ground buildings are still preserved here: fortress walls, towers, prayer houses of the Karaites - kenassas and the mausoleum of the daughter of Khan Tokhtamysh, Janike-khanym, dated 1437.

Janike was the wife of Emir Edigei and became a prominent political figure in the disintegrating Golden Horde. Several legends are associated with her name. According to one of them, Janika, trying to help the besieged Chufut-kala, carried water from a secret well to the city all night. Except for her, thin as a reed, no one could make their way along the underground passage to the well. The next morning, exhausted, Janike died. In the summer of 2001, cavers cleared a part of the underground passage running into a well located outside the city. The course has an offshoot littered with stones, possibly overlooking a plateau. If the move really connects the city with the well, then the legend becomes reality.

The Assumption Cave Monastery is located in the rock opposite Chufut-kale. It was probably founded by monks from Chufut-kale, when the Tatars captured the city in the middle of the XIV century. In the Crimean Khanate, the Assumption Monastery was the residence of the Metropolitan and was revered not only among Christians. There is information that the Crimean Khan Khadzhi-Girey prayed here for help in hostilities. Apparently, the Most Holy Theotokos heard him, and the Giray dynasty remained in power for another 300 years.

After the annexation of Crimea to Russia in 1783, almost all of our crown-bearers visited the Assumption Monastery - Catherine II, Alexander I, Nicholas I, Alexander II, Nicholas II. In Soviet times, the monastery fell into decay, but in recent years it has been rebuilt.

IN THE VALLEYS OF KACHI AND BODRAK

Cave cities lie mainly in river valleys. A prominent Russian ethnographer P. Koeppen wrote in 1837: "Having passed under a canopy of a rock, you are in a charming narrow valley, where … caves, dug up on the top of the mountain, testify to the caring activity of some unknown inhabitants who labored here for an unknown reason."

We are talking about the valley of the Kacha river and about the Kachi-kalon cave monastery. Here you can see the remains of churches, but the greatest interest is a huge amount (about 120) grape pressures. Some researchers attribute the flourishing of winemaking to the time of the Khazar Kaganate (to the VIII-X centuries). The monastery appeared in this place not earlier than the XI century and continued to operate, receiving material assistance from the Russian state even after the Crimea was captured by the Turks. This happened at the end of the 15th century, and gradually the cave monasteries fell into disrepair. In the following centuries, only shepherds with goats and sheep wandered here, fleeing in cool caves from the scorching sun.

Above the Kacha mountain is Tepe-Kermen. The heyday of the city, spread out on its top, falls on the XII-XIII centuries. The unique building of Tepe-Kermen can be called the “Church with a baptistery”. It owes its name to an unusual cruciform font. The spacious dimensions of the church suggest that it served as the main cult center of the city. Many tombs were carved in and around the church, however, as in other cave cities, all of them were opened and plundered long before the advent of travelers in these places - true lovers of history who sought to penetrate into the past of Crimea.

In the Bodrak valley, in the cliff of the Baklinskaya cuesta, one can distinguish the caves of another settlement. This is a settlement of farmers and winegrowers, which became a small urban center in the X-XIII centuries. The Baklinskoe plateau of two tiers turned out to be a good refuge: local residents built houses on the lower tier, and the upper one covered the city from the steppe side and made it invisible to nomads.

Bakla is located on the outskirts of the Middle Ridge. From its top one can see the distant houses of Simferopol and the steppe stretching to the horizon, the mountainous country of the Middle Ridge and the pale purple silhouettes of the Main Ridge. All the versatility of Crimea is felt here. Various landscapes, cultures, eras are intertwined on this small piece of land …

A. GLAZOVA