Imagine a physicist sitting in a cage with a gun pointed directly at his head. The direction of the spin of a random particle in the room is measured every few seconds. If the spin is in one direction, the gun fires and the physicist dies. If to the other, then only a click sound is heard and the physicist survives. So the chances of a physicist surviving are 50-50, right?

Everything may not be so simple if we live in a multiverse - that is, besides our universe, which we call our own, there are many others.

This scenario with a physicist and a gun begins the famous thought experiment called “quantum suicide,” and this is one way to try to understand if we live in only one of many (and potentially infinite) universes.

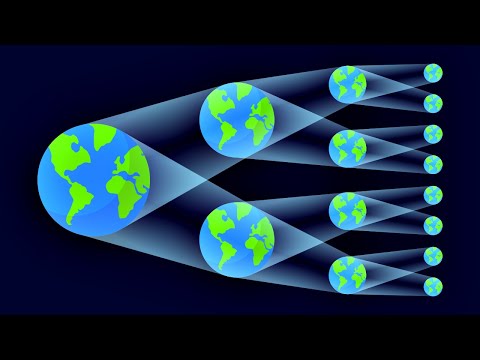

This thought experiment relies on quantum mechanics and the idea that there is no single objective reality. Everything that we see around us is just one of the possible configurations of all the probabilities that this or that event will occur. One interpretation of quantum mechanics is that all other sets of probabilities can exist in their own separate universes. So if you follow the thought experiment, given this interpretation, then when you measure the second particle, the universe will split into two, each of which will have its own possible version of the occurrence of events: in which the physicist lives and in which the physicist died.

His survival is now tied to quantum probability, so he seems to be alive and dead at the same time - just in different universes. If a new universe splits every time a particle is measured, and the gun either fires or doesn't, then in one of those universes, the physicist will eventually survive, say, 50 particle measurements. This can be compared to a coin thrown 50 times in a row. The probability that 50 times in a row will come up tails is extremely small, but it is - the chance tends to zero.

And if this happens, the physicist will understand that the multiverse is real, and in a particular case - in the described experiment - the physicist is truly immortal, since the gun will never fire. But he will also become the only person who knows that these parallel universes exist. And how many physicists will have to "spend" to find out for sure.

However, there are other, more intelligent versions of multiple universes that are mathematically backed up and potentially testable.

"For some people, parallel universes are like jumping through a portal to another world or something like that," says Matthew Johnson, a physicist at the Perimeter Institute. "But that's completely different."

Promotional video:

Actual observable evidence of multiple universes will be difficult to find, but possible. And this is how physicists plan to do it.

Multiverse versions

In fact, there are quite a few theories of a multiple universe, and the multiverse from a thought experiment with "quantum suicide", where every possibility becomes reality, is one of the most radical.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicist Max Tegmark suggests breaking multiple universe theories into four different types to make it easier to think.

We will focus on the first level of the multiverse - these versions are easier to understand than others. At the first level, we also have a pretty good chance of finding evidence that proves that the multiverse is real.

Multiple universes derive from the mathematical predictions of pre-existing theories, and a Level 1 multiverse is predicted by a highly respected and powerful idea in physics: inflation.

What do we mean by "the universe"?

To understand the idea of multiple universes, you first need to define what we mean when we say "universe." Our definition of the "universe" has changed more than once, for example, when we invented the first telescope, looked out into space and learned that stars are not attached to the sky by nails, and the Earth is not alone in space.

But the universe is much larger than we can see through a telescope, Johnson says. Our universe is only a sphere of light that has had enough time to reach us. If we wait another billion years, we will see even more and our concept of the universe will turn upside down again, Tegmark says.

Someone standing on a planet trillions of light-years away will have a completely different picture of the "universe" based on how much light has hit their planet.

There is no way we can reach these other bubbles of universes by definition, because there is no way to travel faster than light. Although we cannot see them, physicists believe that traces of their birth can still be found.

Where is the proof?

The idea behind inflation is that during its inception, our universe went through a period of rapid expansion (immediately after the Big Bang), when a nanometer of space suddenly exploded 250 million light years in less than one trillionth of a second.

Once inflation began, it never completely stopped. In some areas of space-time, it stops, in which areas of space turn into bubbles, like the universe that we see around, but in other places, space continues to expand. If the expansion is infinite, and many believe so, then new bubbles of universes are constantly forming. This leaves a bubble trail. We drift through space-time in the foamy jacuzzi of universes.

Again, there is no way to communicate with these other bubble universes, because we cannot travel faster than light. But theoretically we can prove that they exist. And here's how.

When our bubble universe first formed, it is possible that it collided with other bubble universes that are forming around ours. It is unlikely that we are still near them, since the ongoing expansion of space-time carries us further and further.

However, the effects of early collisions could have rippled the cosmic microwave background (heat from the Big Bang). In theory, we could spot these ripples with telescopes. It would be a discolored disc - like a bruise on the body of a microwave background.

Jones is looking for such "bruises", but a lot depends on how quickly other bubble universes appeared and how many of them there may be. If there are few bubbles, we might not have encountered them at all.

The Planck Space Telescope is currently listening to the skies for evidence of such collisions with other universes.

The multiverse inside the LHC

Different physicists hold different theories of the multiverse. This version arises from string theory, as well as the idea of the existence of many other dimensions to which we simply do not have access (as in the situation in which the hero of McConaughey got in the movie "Interstellar"). Some physicists think that parallel universes are hiding in these extra dimensions.

This idea of a multiverse is also testable

Physicists will be looking for microscopic black holes at the Large Hadron Collider, which recently went into operation. The LHC cannot produce a black hole that will be dangerous, but according to this theory, it is possible to create microscopic black holes that will instantly evaporate. The presence of black holes would mean that the gravity of our universe is seeping into extra dimensions.

“Since gravity can flow out of our Universe into extra dimensions, such a model can be tested by discovering miniature black holes at the LHC,” said physicist Mir Faisal. “We've calculated the energy at which to detect these black holes in the gravitational rainbow. If we find black holes at that energy, we know that both the gravitational rainbow theory and the extra dimensions theory are both correct.

This would be compelling evidence for string theory and parallel universes, and also help explain why gravity is so much weaker than other fundamental forces.

However, there is no serious confirmation yet. Only doubts

“I believe only in what is supported by concrete, testable experimental evidence, and the concept of parallel universes cannot exactly boast of this,” says Brian Green, a theoretical physicist at Columbia University.

The problem is, Johnson says, that physicists are moving away from philosophical discussions of multiple universes. Some just want to test the idea. Others hold radical and untestable theories. Tegmark says he will try to experiment with quantum suicide when he is old and frail. But let's hope he's just kidding.