A monstrous virus spreads across the planet in a matter of weeks. There are no medications, there is practically no chance of not getting sick. Villages die out one after another, in cities only ambulances move along the streets. The dead are buried in mass graves. And when the peak of disease subsides and survivors find hope, the world will be covered by a second, more deadly wave of the pandemic.

This is not a Hollywood blockbuster script or apocalyptic fiction. A hundred years ago, a virus barely discernible in microscopes passed through the planet - and killed more people than the First World War, which was underway at the same time. It appeared in the summer, and not in the winter, as usual, killing beggars and presidents, young and healthy - almost faster than the old and weakened, and outside the laboratory it usually only infected people. It has a medical name, but survivors remember it as "Spanish flu." Or even simpler - "Spanish".

He came from nowhere …

Spanish flu, influenza, Flanders Gripe, Blitzkatarrah … it is still not known exactly where and when this virus first appeared. Its structure is similar to the so-called "bird flu", and one of the most famous versions of its origin is a disease in one of the military camps, where chickens and pigs were raised for soldiers. However, this time the pigs were "out of business", the virus went directly to humans.

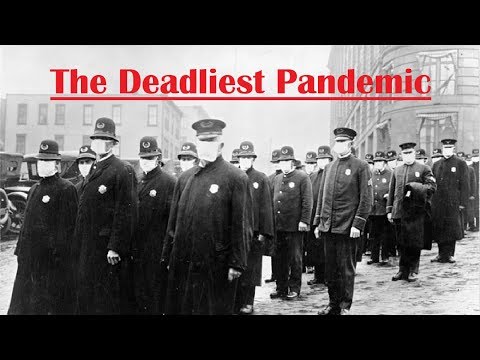

Promotional video:

There are other hypotheses about its origin - in particular, "Chinese". In 1917, an epidemic similar in symptoms was observed in China, and when the Entente countries hired nearly one hundred thousand Chinese, the virus arrived with them in Europe. In the first months, its influence was almost imperceptible against the background of other wartime deaths - everyone was already accustomed to the fact that in damp and cold trenches soldiers mow not only shrapnel and poisonous gases, but also diseases.

Military camps, through which tens of thousands of people passed every day, and hospitals were overflowing with wounded and sick soldiers, became simply ideal centers for the spread of the disease.

The first reports of a new fatal disease appeared in France at the end of 1917, and already in January 1918, the disease reached the United States. However, due to the ongoing war, the data on the spread of the disease were of an official nature - "to maintain the morale of society" the messages were adhered to by censors. Only when the epidemic reached neutral Spain, where no military censorship was introduced, the scale of what was happening became clear from the information in the press. But by this time it was too late to try to stop the virus.

But due to the fact that it was Spain that first openly began to report the epidemic, the new flu received a "Spanish residence permit" - although in reality he had about the same relation to this country as the witcher Geralt to Rivia.

Disease is a matter of young people, a cure for wrinkles

The first wave of the disease resembled the already familiar flu epidemics - the sick, the elderly, and the weak were at risk. But after a few months, the virus has changed. Now young people were dying from it, the peak of mortality was in the age group from 20 to 40 years. In addition to pneumonia associated with the flu, the virus killed itself: the cause of death was cytokine storms - an excessive reaction of the body's immune system.

The wicked irony of fate was that the stronger the patient's immune system, the greater the likelihood of death. The fact that the black and blue victims of the new infection were somehow connected with the previous wave was only guessed because those who had recovered from the previous version of the strain received immunity.

In the summer of 1918, for a soldier - it doesn't matter whether the Entente or the Central Powers - the chance of survival at the front could be even higher than at the rear. Enemy shells and bullets could hit or fly by. But if a person got sick, ambulance trains took him to the already overcrowded hospitals with infected.

Lingering shot

The First World War ended in 1918 - but this did not stop the epidemic. On the contrary, soldiers returning from Europe brought a fatal illness even to places where the flu had not reached before. At the same time, it turned out that under certain conditions, the mortality rate can be significantly higher than usual. For example, in Alaska, one schoolteacher reported that in her area, three settlements died out completely, in others - an average of 85 percent of deaths. Here, to the deaths from the disease itself, the fact was added that sick people could not hunt and even collect firewood - and died of hunger and cold.

However, it was no easier in the southern states. So, in Connecticut, the first cases were noticed on September 11. Two weeks later, there were two thousand, then nine thousand, and by the end of October - 180 thousand. The death toll at its peak was 1,600 a week, although, as the state health minister said in a 2006 report, “The total death toll will never be known. The reports are incomplete, the epidemic was too severe."

The same thing happened in other states. Schools, libraries, theaters and churches were closed, and all kinds of public gatherings, including funerals, were prohibited. Even the sale of drinks "on tap" was prohibited - except for the use of carefully sterilized dishes.

But all this was of little help. The gauze masks with which they tried to protect themselves, as studies have shown, had near-zero effectiveness. There was no medicine either, although in search of a cure for the disease, the doctors "tried everything they knew." The city streets were empty, the healthy people were afraid to go out into the streets. To the modern fan of Hollywood production, this would look like a zombie apocalypse, but without the zombies.

And every day there were more and more of them.

The only type of treatment that showed at least some positive effect was blood transfusion from those who had already recovered to the sick.

The exact number of victims of the "Great Pandemic" is unknown even for the well-off by the then standards of the United States - only rough estimates, from 500 thousand to 675 thousand dead. The data for other countries is even more approximate. For example, in China: for some time it was believed that only port cities suffered in it, but the study of missionaries' reports showed that the Spanish flu penetrated into the central regions of the country. But if in densely populated India, the British colonial administration was engaged in at least some kind of calculation, then no one counted the dead Chinese.

Roughly the same thing happened in Russia, engulfed in the Civil War, where the official data about 270-300 thousand deaths are unlikely to be related to the real scale. Modern researchers agree that the total number of victims of the "Spanish flu" can reach up to one hundred million - from three to five percent of the then population of the planet.

… and went nowhere

After the peak of the "fatal second wave", the number of cases began to decline sharply - in a few weeks their number fell from thousands to almost zero. The next few "waves" - US doctors usually write about four, the last one passed through the country in 1920 - were less lethal. Then the virus disappeared.

The exact reasons for the disappearance of the "Spanish flu" are as mysterious as its appearance. Perhaps the virus quickly mutated to a less lethal one, and some of the strains that make us suffer from a cold every fall for several days has a direct relationship to the "black plague" that wiped out millions of people a hundred years ago.

But this is just one of the theories - the history of the Spanish woman is still full of mysteries, to which there are no 100% accurate answers. As well as the main question: can the virus come back again?

Andrey Ulanov