The ice caps of the Earth began to retreat and advance every 100 thousand years in the distant past due to the almost complete stop of the "conveyor" of currents off the coast of Antarctica and a sharp decrease in the proportion of CO2 in the atmosphere. The evidence for this has been published in the journal Science.

The modern ice age in the history of the Earth, as geologists today believe, began about 2.6 million years ago. Its main feature is that the area of glaciation and the temperature of the Earth's surface throughout its entire length were not constant. In other words, the glaciers were constantly retreating and advancing. These cycles of glaciations and "thaws", as many scientists today believe, are primarily associated with the so-called Milankovitch cycles - the "rocking" of the Earth's orbit, changing how much heat is received by the poles and temperate latitudes. Other geologists and climatologists believe that, in fact, these abrupt climate changes are associated not with "space", but completely terrestrial factors, such as restructuring of the "conveyor" of currents in the oceans or a sharp increase or decrease in the proportion of CO2 in the atmosphere.

The so-called "hundred thousand-year problem" is especially controversial between the supporters of these ideas. The fact is that in the first half of the ice age, the length of these cycles was about 40 thousand years, which fits well with the theory of the supporters of the "cosmic" origin of the ice age.

About 1.2 million years ago, the situation changed dramatically, and glaciers and thaws began to replace each other every 100 thousand years. The reasons for this are not yet clear, which causes controversy even among the supporters of the "climatic" theory of glaciation.

Adam Hasenfratz of the Swiss Graduate School of Technology in Zurich and his colleagues found the first definitive answer to this question by studying sediment samples dug from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean around the southern Bouvet Island, one of the most isolated pieces of land in the world.

These deposits, the scientists explain, have been forming at the bottom of the Atlantic over the past 1.5 million years, and inside them are microscopic shells and other remains of algae and plankton that lived in ancient seas.

Fluctuations in water temperature, as scientists explain, have a strong effect on the chemical and isotopic composition of the shell of some algae and zooplankton, which makes it possible to use their sediments as a kind of "climatic chronicle". It allows you to find out not only how the temperature of the waters of the seas and oceans changed in the distant past, but also to understand in which direction and how the currents moved.

In this case, two deep polar currents pass through this point, washing the foot of Antarctica and playing an important role in the water cycle between the upper and lower layers of the ocean.

Having reconstructed the history of their activity from the remains of algae, scientists found that in the first half of the ice age, the differences in water temperature between them were relatively small. This suggests that the deep and near-surface waters of the Atlantic were actively mixing at that time, which prevented the "burial" of large amounts of CO2 in the ocean.

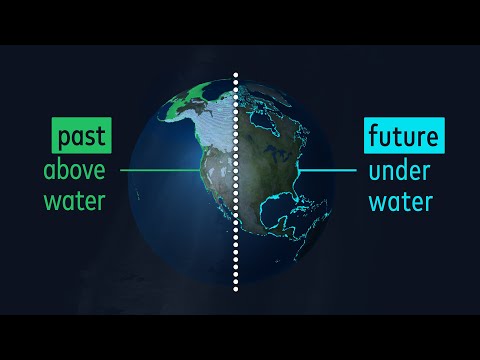

Promotional video:

About 1.2-1.1 million years ago, the picture changed dramatically - the differences between the layers of the ocean began to grow rapidly, and the deep layers of water almost stopped rising to its surface. Such a weakening of the circulation of currents should have led to a sharp decrease in the proportion of CO2 in the atmosphere due to the fact that it turned out to be "walled up" in the deep layers of water.

All this, as scientists suggest, strengthened and extended the periods of glaciation, increasing their length from the classical 40 thousand years predicted by Milankovitch cycles to the actual 100 thousand years.

Interestingly, something similar - the weakening of the cycle of currents and the "mixing" of water between the deep and surface layers of the ocean - is happening today. If these trends continue, they may not only slow down global warming, but also affect the climate in the most unpredictable way in the coming centuries.