Warning: This article contains spoilers for the new TV series "Stranger things"

The new series "Stranger Things" is not just a nostalgic picture that throws us back to the 80s, but a special vision of the hypothesis of the existence of parallel universes, which largely coincides with the vision of modern science. The essence of the series is that several children are trying to understand the chain of mysterious phenomena and disappearances that have occurred in a small town. They soon realize that everything is much more complicated than it seems, and a series of strange incidents is the result of the interaction of parallel universes.

Of course, the particular picture of the universes that is shown in the series is unlikely to take place, but the very idea of the existence of parallel worlds is no longer new.

The idea of the existence of two parallel universes, somewhat different from each other, has already been explained by the hypothetical features of quantum mechanics, gravity and other scientific fields and phenomena. This does not mean at all that a universe inhabited by monsters and other strange creatures must necessarily exist not far from ours, because no scientific theory has been 100% proven. But the very fact that the existence of several universes, according to scientist Brian Green, "does not contradict the laws of physics", is already arousing keen interest.

More fantastic than fiction

According to the plot of the series "Stranger Things", the inhabitants of the town of Hawkins, in Indiana, find themselves in dangerous proximity to the parallel universe "On the contrary", which is full of death and decay, and, moreover, is inhabited by monsters and covered with some unprecedented green mud moss. And so, one of the monsters somehow seeps into our universe. From this moment, the adventures of local residents begin, who enter the parallel universe through the stumps and communicate with it, flashing lights in the houses. Among other things, the series pleases with the presence of extrasensory abilities in the heroes, Soviet spies and all those attributes of the cinema of the 80s that we so lacked.

Despite the fact that the show itself is just a little creepy fiction and fantasy, the idea of parallel universes fits at least one scientific theory. We are talking about Hugh Everett's theory of multiple worlds based on quantum mechanics (one of the teachers in the series just refers to this scientist).

Promotional video:

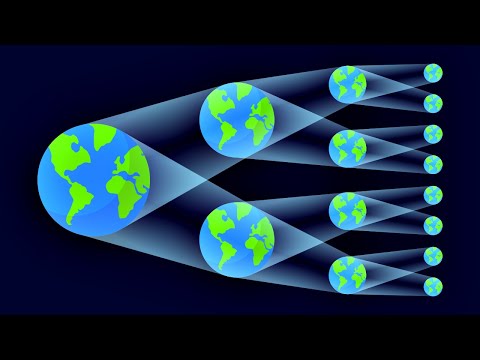

Hugh Everett is a physicist who put forward in the 50-60s of the last century the hypothesis that the universe can be duplicated with each of our decisions. So, we look at our shoes, deciding whether they are dirty or not, and, having come to the conclusion that they are dirty, we put on the shoes. At the moment when we made a decision, we split into several options in some way. To one of the options, the shoes will seem clean, after which this our "double" will simply put on these very shoes and go about their business. So the universe is constantly multiplying into several copies.

True, it should be noted that, according to Everett, the newly emerging theories could not interact with each other in any way - in the series this interaction is more than possible.

Many interacting worlds

Recently, University of Texas physics professor Bill Poirier put forward a kind of improved version of Everett's theory (this idea was described in detail in the journal Physical Review X in 2014). The main difference between Poirier's theory is the possibility of interaction between parallel universes and the absence of the concept of multiplication of these universes from time to time - these universes already exist.

But Poirier's version does not fit the series either. Bill Purier argues that neighboring worlds are very little different from each other and resemble a stack of pancakes. Any change visible to the eye means that the universes are at a very great distance and cannot interact.

In the series, the worlds are completely different, which means that they cannot coexist in any way, which means that creatures from these worlds can neither interact with each other, nor travel from one world to another.

Membrane theory, Swiss cheese and space loaves

In general, there are probably as many theories about a plurality of universes as there are universes themselves, according to these theories. But they all have one serious drawback - not a single assumption has been fully proven.

“I am quite skeptical about hypotheses about the existence of parallel universes,” says Brian Green, and immediately adds: “… but the idea itself is simply amazing! Many theories emerge from the data we already have."

Brian immediately cites the well-known Big Bang theory as an example. Its essence boils down to the fact that more than 13 billion years ago there was not one big explosion that created our universe, but several. And if there were several explosions, then there are also several universes.

Thus, the structure of the cosmos can be compared to Swiss cheese, where each hole is a separate universe. From time to time, these universes could collide, creating microwave radiation, leaving traces that we can sometimes notice.

Another version belongs to the group of string theories - one of their membrane models. According to her, our universe resembles a piece of bread in a cut space loaf. Thus, we are surrounded by other universes - other slices of this loaf.

At the end of the conversation, Byne Greene concludes: "If we really live in a world consisting of universes intersecting with each other, it will not be surprising that a microparticle, separated from a proton in a large hadron collider, will move from our universe to the neighboring one."

Anna Kiseleva