If we assume that the body needs sleep to rest, then the purpose of dreams is completely incomprehensible. Why is the brain, instead of resting, actively working, making up stories (often scary or unpleasant)? Why does he scare himself, drive himself to despair, drive himself into dead ends, and then return to a waking state? Is there a benefit even from nightmares?

The man tried to understand these issues for a long time. Already in the 5th century BC. e. the Greek poet Paniasis wrote a guide to the interpretation of dreams, containing a general theory and explanation of individual dreams. At the time of Alexander the Great, the Athenian Antiphones described in the book many dreams with indications of how correctly they were interpreted.

Unfortunately, only a few passages have survived from the writings of the ancient dream specialists. The oldest, completely extant, dream book was compiled in the 2nd century AD. e. Artemidore of Lydia. In the 17th century, this book was translated into English. It became a bestseller and had gone through 32 editions in England by 1800.

However, with the development of science and education, the attitude towards dream books has changed. They and their naive readers were ironic. But in the 19th century, works unexpectedly began to appear that claimed a scientific approach in explaining dreams.

Thus, in 1814, a book by the Munich specialist on the philosophical foundations of natural science Gothilf Schubert "The Symbolism of Dreams" was published in Germany, and in 1861 Karl Albert Scherner's work "The Life of a Dream" appeared. It contained discoveries that were later confirmed by psychoanalysis, albeit by fundamentally modifying them.

In the middle of the 19th century, the French physician Academician Alfred Mori took up the scientific study of dreams. After carefully studying over 3000 dream reports, he concluded that the content of dreams can be explained by external influences. For example, at night an object falls on a person's head, and the one who wakes up with horror recalls that in a dream the revolutionary tribunal sentenced him to death, and the guillotine knife cut off his head.

But are there really no closer associations with a blow to the back of the head? Indeed, during the time of Maury, the era of the French Revolution had become a thing of the past, and the guillotine was hardly one of the subjects that a person often thought about or with which he dealt.

Promotional video:

On the other hand, the famous American philosopher Ralph Emerson (1803-1882) approached the explanation of dreams. He argued that an experienced person studies dreams not in order to predict his future, but in order to know himself. This idea is most fully developed by the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), whose book The Interpretation of Dreams appeared on the shelves of bookstores in November 1899.

According to Freud, a dream does not portend anything and does not have the slightest relation to the future. It contains the past and the past. Sleep analysis makes it possible to understand the hidden aspirations and fears, the roots of which are very difficult to get to in other ways.

A person often has strong desires that contradict his upbringing and psychological attitudes. He is afraid to admit them to himself. During the day, when a person is awake, these unattainable desires are sent to the area of the unconscious and are there under the reliable protection of "censorship". The state of sleep causes a redistribution of psychic energy.

The sleeping person is deprived of the opportunity to act and fulfill his desires, he does not need to spend energy on eradicating harmless hallucinations. The only harm they can do is sleep interruption. Therefore, desires in a dream are not extinguished, but only translated into a special symbolic language necessary in order to deceive the "censorship", which does not allow anything forbidden into consciousness.

Thus, a compromise is reached: passions boil in a dream and forbidden scenarios are played, and after awakening they are forgotten or remembered in such a distorted form that they seem completely meaningless. Dreams in the ideas of people of different cultures are strongly associated with dreams and fantasies. It is not surprising that psychoanalysis has transformed the interpretation of dreams into the interpretation of fantasies and dreams, and the images of dreams into symbols and objects of passionate harassment.

But the American psychologist Calvin Hall (1909-1985) approached the creation of dreams as a creative intellectual cognitive process that does not require any special abilities or special training from the sleeper. Unlike Freud, Hall's dream is centered on thoughts. But not about anything. In any case, not about politics and economics.

Hall was engaged in researching the dreams of his students in the days when the Americans dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. This event was not directly reflected in any of the analyzed dreams. Major sporting events, presidential elections, clashes of interests of superpowers, on which the future of the world depends, were also ignored by dreams.

Therefore, Hall came to the conclusion that in dreams people, as a rule, deal not with intellectual, scientific, cultural, or professional problems, but with their inner world. Dreams express a person's thoughts about himself and his desires, about the people with whom he communicates, about prohibitions and punishments for violating them, about life's difficulties and ways to achieve goals.

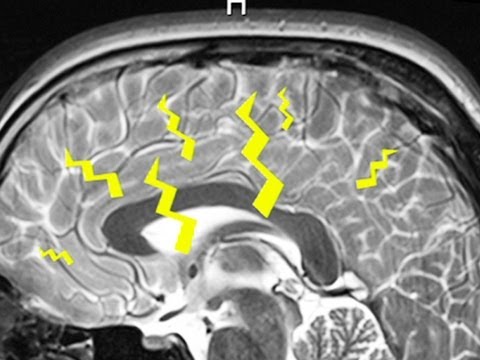

However, as it turned out, when explaining the mechanism of dreams, one can do without human feelings, thoughts and aspirations. The brain stem contains a "dream generator". He regularly, as on schedule, turns on and begins to "bombard" the cerebral cortex, that is, to activate nerve cells in some of its parts.

The choice of objects to be bombed (as opposed to the operating time of the generator, which can be calculated with a high degree of accuracy) is completely random. Excited areas of the cerebral cortex produce dreams, the beginning and duration of which are programmed, and the content is devoid of any meaning. Random pictures replace one another, like in a kaleidoscope.

According to Harvard scientists, dreams have no special purpose. They only accompany a vital physiological process that regulates brain function. Should we be surprised at the illogicality of dreams and come up with psychoanalytic excuses for their quirkiness?

This theory has caused a storm of protests from psychologists. Indeed, it is difficult to believe that dreams, which are often very complex and skillfully constructed, are the result of random processes. It is also unclear how the same dream is sometimes repeated several times …

For a whole day of running, bustle, work or even rest, a person receives a lot of information that he, quite possibly, will never use in his life, but which he nevertheless carefully stores in his memory. The brain cannot sort it out all the time. He mechanically takes a lot of unnecessary things and runs the risk of becoming like a closet overflowing with useless rubbish, in which nothing can be found.

A person constantly uses information from his memory. So, in order to remember something, he must each time sort through, view and think over everything that his brain has managed to accumulate? People have painful memories. Each touch to them can cause mental trauma. However, a healthy person lives with them and does not experience any particular inconvenience. People don't forget anything. They only put marks on certain parts of their memory: do not look here.

Unnecessary information, assimilated during the day, can stick out in the brain like a thorn. It becomes the cause of the emergence of new harmful connections between individual parts of the cerebral cortex. In addition, it activates nerve cells, which entails fantasies and obsessions.

In 1983, Nobel laureate biophysicist Francis Crick and mathematician Grame Mitchison suggested that the purpose of dreams is precisely to destroy these harmful connections, and with them burdensome fantasies. Dreams help you to forget the excess that has entered the brain during the day.

Thus, there are many hypotheses regarding the origin and role of dreams in human life.

And in this list, the hypothesis of the French logician and specialist in the theory of science Edmond Gobleau, who in 1896 suggested that dreams do not exist at all, stand apart.

To a person, when he wakes up, it seems that he is recalling the events that he saw during his sleep. It seems to be quite obvious: in reality this did not happen, so it was a dream. However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that imaginary dreams, in whole or in part, are constructed during a short period of awakening and at the very beginning of wakefulness.

It can be assumed that during sleep (both fast and slow), no mental processes occur. Consciousness is completely disabled. But here it gradually wakes up. It again includes images of the surrounding world. They need to be reordered to such an extent that they can be operated on. What we used to call dreams is in reality a kind of morning mental gymnastics, a daily adaptation of consciousness to reality.

Edward Walpert of the University of Chicago recorded the electrical potential in the muscles of the limbs of the sleeper. First, excitement was noted in the right hand, then in the left, and then in the legs. The sequence of muscle activation was found to be in good agreement with sleep. The sleeper had a dream: he first held a bouquet of flowers in his right hand, then took it in his left and went somewhere. Do such experiments contradict Goblo's hypothesis? Hardly. The dream could arise some time after the activation of the muscles (which could be accidental) and retroactively "explain" the reason for the muscle activity.

But what, then, does the periodic rapid eye movements mean? In order to follow the events taking place in a dream, eyes are not needed. Their movements can be explained by the physiological processes studied by A. Hobson and R. McCarley.

Goblo's speculation seemed a bit too radical. At the same time, he pushed his way for psychoanalysis with his doctrine of the intense psychic work of the unconscious, which never dies down and manifests itself in night dreams. The strange hypothesis was forgotten for a long time. Recalled her in 1981 by Calvin Hall, which was discussed above.

Studies of biochemical processes occurring in various parts of the brain shed light on the physiological mechanism of sleep, but give little to understanding the nature of dreams. Psychoanalysis proceeds from the premise that dreams become the culmination of the dramatic struggle of passions in the unconscious. However, Goblo's hypothesis suggests that it is legitimate to look at dreams from a different point of view. They are not the end, but the beginning of the mental process.

Psychoanalysis insists on the sexual nature of most dreams, explaining this by the fact that each person has a great variety of forbidden desires, driven into the unconscious and striving for freedom. But in reality, dreams are much more varied. For example, chase scenes are often present in them, but it is unlikely that anyone would think to explain this by the widespread latent persecution mania.

But what if the dream is not a mirror at all, which reflects our mental conflicts and trauma? What if he has his own special purpose, not at all related to mental illness?

Dreams cannot tell anything not only about the future, but also about the past and the present. They are unable to reveal to us the secrets of the unconscious, because they are not means of communication. The sleeper does not need semantic information - after all, he is deprived of the opportunity to process it.

Apart from a small number of funny, but vague stories about wonderful scientific ideas and discoveries that came in dreams, there is not even a hint that a person is able to solve even the simplest problem in a dream.

Let's imagine that sex, scenes of violence, disaster and chases are not an end in themselves, but just a building material. They are the stuff from which dreams are woven, but in no way are dreams. And they penetrate dreams not because during sleep the blind "censorship" that has lost its vigilance is unable to see them under primitive masks and keep them within the unconscious, but because there is a need for them. But why can't a person find material that gives more pleasure to construct his dreams?

After analyzing 10,000 dreams, Hall concluded that 64 percent of them were associated with sadness, apprehension, fear, irritation, anger, and only 18 percent were associated with joyful and cheerful feelings.

If the sleeping person, consciously or unconsciously, himself participates in the choice of subjects for his dreams, why should he have nightmares? One can, of course, try to explain the prevalence of excruciating dreams by people's fear of life, but why do we persist in talking “like in a dream” about something unusually good, ignoring the experience that tells everyone that dream adventures are usually not very pleasant?

Scenes of sex, violence, catastrophes in a dream play the role of stimuli that excite the imagination, although they cause completely different reactions that would stimulate in life. According to the principle of functional autonomy, developed by the American psychologist Gordon Allport, incentives break away from their biological or social roots and begin to live an independent life. Man yearns for the sea. In his youth, he earned money by hard work as a sailor and cursed his fate, now he is a wealthy banker, troubles are forgotten, and the sea causes nostalgic feelings.

Sexual scenes in dreams do not have to be related to sex drive, and violent scenes to repressed "brutal" desires. The dream is not a realistic novel. He has his own logic. There may be no semantic load in its elements. Their purpose is not to communicate information, but to awaken mental processes.

THE USE OF DREAMS UNDER QUESTION

Oddly enough, but recently, some scientists have begun to change their attitude towards dreams. If earlier it was believed that in a dream we solve our internal problems and, as it were, unload the psyche, now scientists even talk about some dangers of dreams. According to the new theory, it is better if there are no dreams at all.

Scientists from the University Hospital Zurich came to this conclusion after a 73-year-old woman became their patient. She was hospitalized after a stroke that destroyed blood flow in the occipital lobe of the brain. At first, there was nothing unusual in the consequences of the blow - the patient's eyesight slightly deteriorated, she felt weakness in half of her body.

But a few days later, the woman stopped dreaming. According to scientists, this woman used to see 3-4 dreams a week. But after the blow, she did not see any dreams for a whole year. Yet the absence of dreams did not affect her sleep or brain function in any way. Scientists began to investigate this phenomenon in detail.

A study by scientists has shown that some people can safely live without dreams. In other words, dreams have no useful or real function. This was revealed by the results of monitoring the electromagnetic waves emitted by the patient's brain during sleep - alpha, delta, theta. Researchers recorded these waves every night using an electroencephalogram for more than six weeks. The patient did not report dreams even when she was awakened during the so-called REM sleep phase.

The occipital lobe of the large brain, which was damaged in the patient, probably plays a very important role in the occurrence of dreams. But both the brain stem and the midbrain are involved in controlling REM sleep. In general, it turned out that the woman does not see dreams either during slow or during REM sleep. But at the same time, to the surprise of scientists, the patient sleeps absolutely normally. Does this mean that the absence of dreams is normal?

Scientists believe that it is not necessary to make categorical conclusions: after all, they studied only one single case.

However, it is curious that the British professor Jim Horn came to the same conclusion - about the futility of dreams.

In his opinion, dreams are a movie for our consciousness, which entertains our brain while we sleep. But not all of this "movie" is watched: for example, patients taking antidepressants are often recognized as having no dreams. But these people do not go crazy, they are completely normal and have no memory problems.

And while many of us believe that dreams are good for mental health, they help resolve internal conflicts and in some way “heal the soul, but there is no hard evidence to support this attractive theory of Freud and others.

In fact, dreams can even harm a person. For example, people who are depressed tend to have sad and scary dreams that can only worsen the sufferer's condition the next day. Therefore, it may be even better if a person does not dream at all. After all, there are many cases when patients who have not seen dreams for a year or longer have improved mental health.